The World of Manga: Manga—the vast, dynamic universe of Japanese comics—is today one of the most influential cultural forces in global entertainment. From bookstore shelves in New York and Paris to streaming platforms and mobile apps worldwide, manga has reshaped how stories are told visually, emotionally, and structurally. Yet behind this global phenomenon stands one towering figure whose influence is so foundational that manga history is often divided into “before Tezuka” and “after Tezuka.”

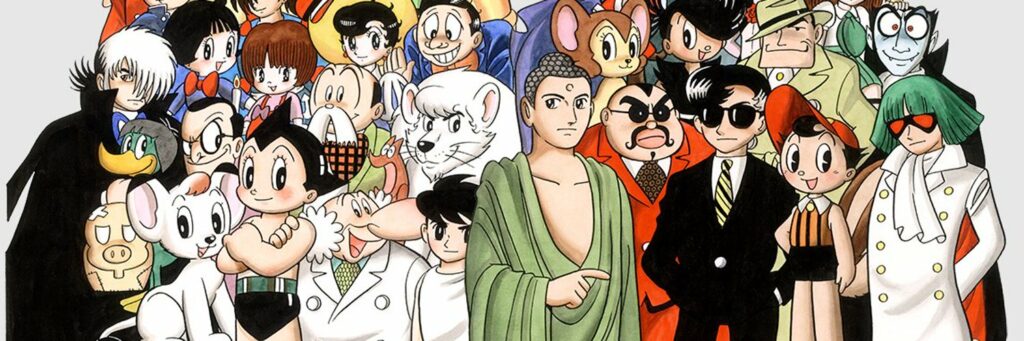

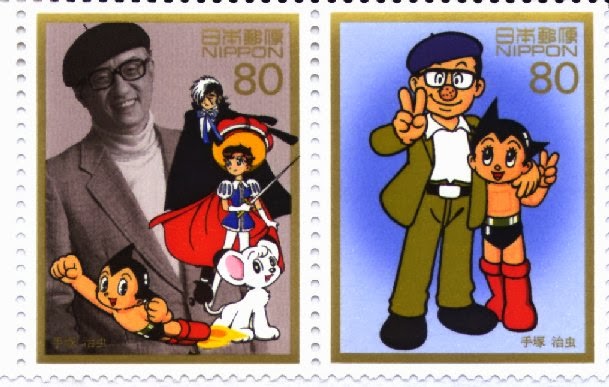

That figure is Osamu Tezuka (手塚 治虫, 1928–1989), widely known as the “God of Manga.” More than a prolific creator, Tezuka was a revolutionary thinker who transformed manga from short, gag-based children’s entertainment into a cinematic, emotionally complex, and philosophically ambitious storytelling medium. His innovations shaped not only manga but also anime, publishing models, and the creative expectations of generations of artists around the world.

To understand manga as it exists today—its visual grammar, narrative depth, genre diversity, and global reach—one must understand Osamu Tezuka.

What Is Manga? A Cultural Medium, Not Just Comics

The word manga is often translated as “whimsical pictures,” but this definition vastly understates its cultural significance. Manga is not a single genre or style—it is a medium, comparable to literature or cinema. It encompasses romance, horror, science fiction, history, politics, autobiography, spirituality, and experimental art.

Before World War II, Japanese comics existed primarily as:

- Short humorous strips

- Political caricatures

- Illustrated children’s stories

They lacked long-form narrative continuity and emotional complexity. That changed dramatically in the postwar era—largely because of Osamu Tezuka.

Osamu Tezuka: Early Life and Formative Influences (1928–1945)

The Early Life of Osamu Tezuka

Osamu Tezuka was born on November 3, 1928, in Toyonaka, Osaka, Japan. From a young age, he showed a keen interest in art, animation, and storytelling. Inspired by the works of American cartoonists like Walt Disney and Max Fleischer, Tezuka began drawing comics at a very young age.

Tezuka’s fascination with animation led him to create 16mm film animations during high school. His determination to pursue his passion for storytelling and animation was unwavering.

Osamu Tezuka was born on November 3, 1928, in Toyonaka, Osaka Prefecture, into a well-educated family. His upbringing combined science, art, and performance, all of which later shaped his work.

Disney, Cinema, and Emotional Movement

Tezuka was deeply influenced by Walt Disney animations, particularly Bambi, which he famously watched dozens of times. From Disney, Tezuka absorbed:

- Expressive character acting

- Emotional clarity

- The idea that drawings could move audiences emotionally, not just visually

Takarazuka Revue and Theatrical Drama

Growing up near Takarazuka, Tezuka frequently attended performances by the Takarazuka Revue, an all-female musical theater troupe. This exposure influenced:

- His dramatic staging

- Costume design

- Romantic storytelling

- The iconic large, expressive eyes later associated with manga

Medicine, War, and Human Fragility

Tezuka’s childhood coincided with World War II, during which he experienced air raids and national collapse. These experiences left him deeply concerned with:

- The fragility of life

- Abuse of power

- The ethical consequences of science and war

He later studied medicine at Osaka University, earning a medical degree—a background that would profoundly shape works like Black Jack and Ode to Kirihito.

The Father of Modern Manga

Osamu Tezuka’s influence on manga extends far beyond his art and storytelling. He played a pivotal role in shaping the manga industry itself. In 1959, he founded the “Osamu Tezuka Manga Juku” (Osamu Tezuka Manga Academy), where he mentored and inspired a new generation of manga artists. Many of his students would become renowned manga artists in their own right.

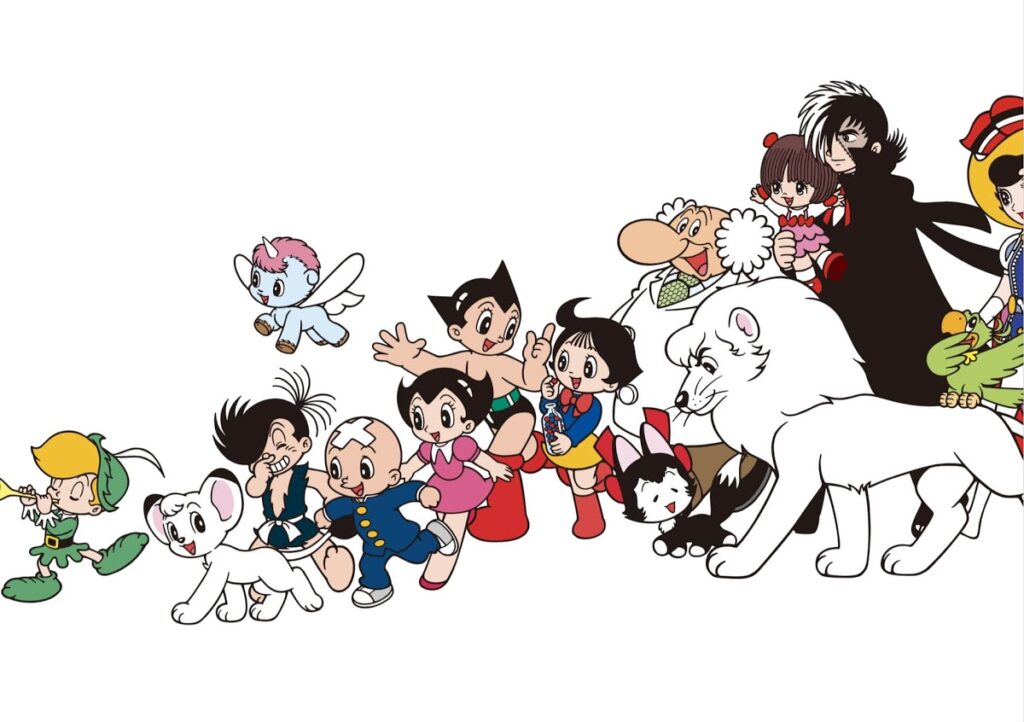

Tezuka’s impact on manga genres was immense. He ventured into diverse themes, from medical dramas (like “Black Jack”) to historical epics (“Buddha”). His ability to tackle a wide range of subjects expanded the horizons of manga and attracted readers from various backgrounds.

The Manga Revolution: “New Treasure Island” and Cinematic Storytelling

In 1947, Tezuka published Shin Takarajima (New Treasure Island), a work often cited as the spark of the postwar manga revolution.

Why It Mattered

- Used cinematic pacing inspired by film editing

- Featured long, continuous narratives

- Emphasized emotional storytelling

- Introduced dynamic panel layouts and visual “camera angles”

This work demonstrated that manga could be:

- Long-form

- Immersive

- Emotionally driven

It fundamentally changed reader expectations—and publisher ambitions.

Astro Boy: The Birth of Modern Manga and Anime (1952–1963)

The Birth of Astro Boy

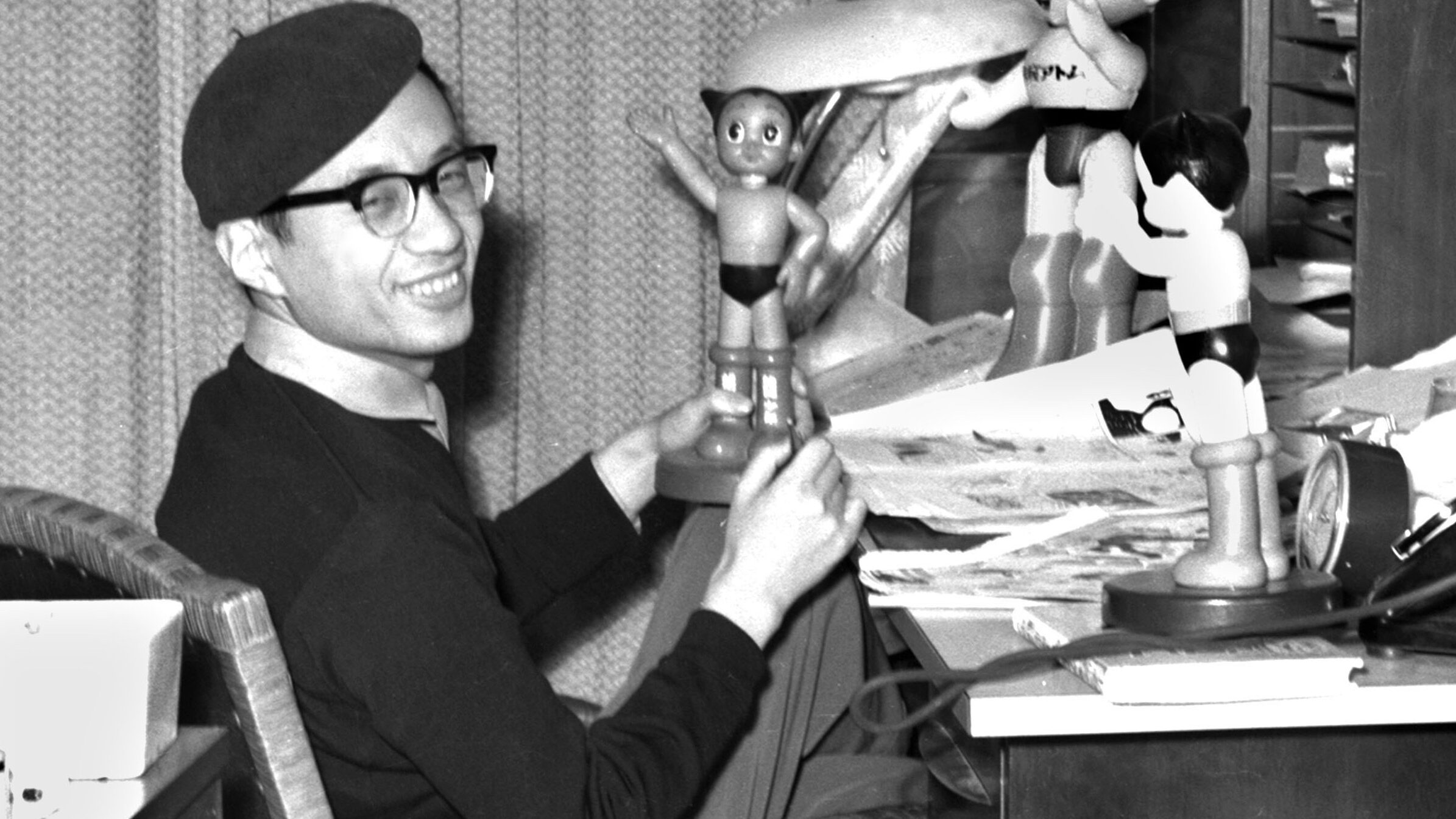

1952, Osamu Tezuka graduated from the Osaka University of Medicine, becoming a licensed medical doctor. However, his true calling lay in the world of manga and animation. He followed his dreams and became a full-time manga artist and animator.

Tezuka’s breakthrough came in 1952 when he created “Tetsuwan Atom” (Astro Boy), a manga that introduced the world to a little robot boy with a heart of gold. Published in the manga magazine “Shonen” (Boys), Astro Boy became an instant hit. This manga began Tezuka’s iconic career and the modern manga era.

Astro Boy’s blend of science fiction, social commentary, and unforgettable characters resonated with readers of all ages. Tezuka’s dynamic artwork and innovative storytelling techniques set a new standard for manga. It wasn’t long before Astro Boy was adapted into the first-ever Japanese animated television series in 1963, solidifying Tezuka’s status as a pioneer in both manga and anime.

From Manga to Cultural Icon

In 1952, Tezuka introduced Tetsuwan Atom (Astro Boy). The story of a robot boy with human emotions captured postwar Japan’s hopes and anxieties:

- Technology vs. humanity

- Justice vs. prejudice

- Power vs. compassion

Astro Boy was revolutionary because it made a childlike protagonist the moral conscience of society.

The 1963 Anime and Industrial Transformation

In 1963, Tezuka’s studio Mushi Production launched the Astro Boy TV anime—widely recognized as the first successful Japanese animated television series.

This series:

- Established weekly anime production models

- Introduced limited animation techniques

- Made anime exportable to global audiences

- Laid the groundwork for Japan’s animation industry

Without Astro Boy, modern anime as an industry likely would not exist in its current form.

The Tezuka Style: Visual Language and Narrative Innovation

One of the defining features of Osamu Tezuka’s work is his unique artistic style. He drew characters with large, expressive eyes, which conveyed emotions and depth like never before. This signature style, inspired by Disney’s animation, became a staple in manga and contributed to its widespread appeal.

Tezuka’s storytelling was equally groundbreaking. He experimented with panel layouts, pacing, and narrative techniques that pushed the boundaries of what manga could achieve. His ability to seamlessly blend humor, drama, and social commentary within a single story was unparalleled.

Tezuka’s influence is not limited to characters—it is embedded in the grammar of manga itself.

Visual Innovations

- Large, expressive eyes for emotional clarity

- Cinematic panel transitions

- Silent sequences for emotional impact

- Flexible page layouts that control pacing

Narrative Innovations

- Long, serialized storytelling

- Character growth over time

- Moral ambiguity

- Blending humor with tragedy

These techniques became industry standards, adopted and adapted by nearly every major manga creator who followed.

Beyond Children’s Manga: Genre Expansion and Artistic Courage

Tezuka refused to be confined to one audience.

Shōjo Manga and Gender

With Princess Knight (Ribon no Kishi), Tezuka helped define modern shōjo manga:

- Gender identity and performance

- Romantic drama

- Strong female protagonists

Medical Ethics: Black Jack

Black Jack explored:

- Inequality in healthcare

- Corruption

- Moral cost of survival

It remains one of the most influential medical narratives in comics worldwide.

Spiritual and Philosophical Epics: Phoenix and Buddha

- Phoenix (Hi no Tori) explored life, death, rebirth, and history

- Buddha retold Siddhartha Gautama’s life as a human struggle against suffering and injustice

These works proved manga could function as philosophical literature.

The Gekiga Era: Tezuka’s Dark, Adult Reinvention (Late 1960s–1980s)

When the gekiga movement pushed manga toward realism and adult themes, Tezuka did not retreat—he transformed.

Works like:

- Message to Adolf

- MW

- Ayako

- Ode to Kirihito

explored:

- Fascism and nationalism

- Sexual violence

- Political conspiracy

- Psychological collapse

This period shattered the myth that Tezuka was only a “children’s creator.”

The Global Reach of Osamu Tezuka

While Tezuka’s work initially gained popularity in Japan, it didn’t take long for his creations to transcend borders. Astro Boy, in particular, became a global sensation. The animated series found audiences in the United States, Europe, and beyond. Tezuka’s storytelling resonated with people from different cultures, further cementing manga’s status as a universal art form.

Tezuka’s impact on global pop culture cannot be overstated. He inspired countless artists and creators worldwide, influencing not only manga and anime but also Western comics and animation. His storytelling techniques and artistic innovations became a source of inspiration for generations of artists.

Global Influence: From Japan to the World

Tezuka’s influence extended far beyond Japan:

- Inspired anime creators worldwide

- Influenced Western animation and comics

- Shaped global storytelling norms

Creators such as Akira Toriyama, Naoki Urasawa, and even Western filmmakers and comic artists cite Tezuka as foundational.

Legacy and Awards

Osamu Tezuka’s contribution to manga was recognized with numerous awards and honors throughout his career. In 1961, he received the Bungei Shunju Manga Award for his work “Adolf ni Tsugu” (Message to Adolf). He was also awarded the Shogakukan Manga Award in 1975 for “Hi no Tori” (Phoenix).

Tragically, Tezuka passed away on February 9, 1989, at 60. However, his legacy lives on through his extensive body of work, his influence on future generations of artists, and the enduring popularity of his characters.

Osamu Tezuka’s impact on the world of manga is immeasurable. He pioneered the art of manga and anime and laid the foundation for the global popularity of these mediums. His innovative storytelling, unique artistic style, and commitment to pushing the boundaries of creativity have left an indelible mark on comics and animation.

Death, Legacy, and Cultural Immortality

Tezuka died on February 9, 1989, of stomach cancer. His final words—often remembered as “Please let me keep working”—symbolize his lifelong devotion to creation.

His legacy endures through:

- The Tezuka Osamu Manga Museum in Takarazuka

- The Tezuka Osamu Cultural Prize

- Ongoing adaptations, reinterpretations, and tributes

- A global manga industry built on his innovations

Osamu Tezuka and the Permission to Dream Bigger

Osamu Tezuka’s true legacy is not a style—it is permission.

Permission for manga to:

- Be cinematic

- Be philosophical

- Be political

- Be emotionally honest

- Be for everyone

Tezuka insisted that drawings could carry the full weight of the human experience—joy and despair, science and spirit, innocence and corruption.

As readers continue to explore manga’s vast and diverse landscape, they do so in the shadow of Osamu Tezuka, the “God of Manga.” His work remains a testament to the power of storytelling and the enduring influence of a visionary artist. In the ever-evolving world of manga, Tezuka’s legacy shines as brightly as ever, reminding us of the boundless possibilities of this beloved art form.

That is why, decades after his death, Osamu Tezuka does not feel like history.

He feels like the beginning.

This post was created with our nice and easy submission form. Create your post!

3 Comments