Charles Monroe “Sparky” Schulz (November 26, 1922 – February 12, 2000) was an iconic American cartoonist best known as Charles M. Schulz for creating Peanuts, the most influential and beloved comic strip in history. His two most famous characters—Charlie Brown and Snoopy—became international cultural icons. Schulz’s minimalist drawing style, emotional honesty, and philosophical depth changed the face of comic art and continue to inspire creators around the world. Beyond the ink and panels, Schulz shaped generations of readers with his timeless observations on failure, hope, identity, and perseverance.

Infobox: Charles M. Schulz

| Name | Charles Monroe Schulz |

|---|---|

| Nickname | Sparky |

| Born | November 26, 1922, Minneapolis, Minnesota, U.S. |

| Died | February 12, 2000 (aged 77), Santa Rosa, California, U.S. |

| Occupation | Cartoonist, Writer, Inker |

| Notable Work | Peanuts |

| Years Active | 1947–2000 |

| Spouse(s) | Joyce Halverson (m. 1951; div. 1972), Jean Forsyth Clyde (m. 1973) |

| Children | 5, including Meredith and Craig |

| Military Service | U.S. Army, 1943–1945 |

| Unit | 20th Armored Division |

| Rank | Staff Sergeant |

| Battles/Wars | World War II |

| Awards | Reuben Award (2×), Peabody Award (2×), Emmy Award (5×), Congressional Gold Medal, Silver Buffalo Award, Lester Patrick Trophy |

| Website | schulzmuseum.org |

Early Life and Education

Born in Minneapolis and raised in St. Paul, Minnesota, Schulz was the only child of Carl and Dena Schulz. His father was a barber, and his mother a homemaker. The Schulz family led a modest life during the Great Depression, a backdrop that influenced Schulz’s appreciation for the quiet struggles of everyday people. Nicknamed “Sparky” after a horse in the comic strip Barney Google, Charles showed an early passion for drawing. His early sketches often featured the family’s black-and-white dog, Spike, who served as the inspiration for Snoopy.

Despite being shy and academically advanced—he skipped two grades—his artistic talent stood out. He spent much of his free time reading the Sunday comics and copying the styles of cartoonists he admired, such as Roy Crane and Milton Caniff. He sent a drawing of Spike to Ripley’s Believe It or Not! in 1937, which was published with the credit to “Sparky,” giving him his first national recognition.

After graduating high school in 1940 from Central High School in St. Paul, Schulz found himself at a crossroads. His mother, who was suffering from cancer, encouraged him to take a correspondence course with Art Instruction, Inc., a decision that became foundational for his career. He would later credit the school for helping him understand the technical skills of cartooning as well as the professional mindset required for success.

Schulz’s drawings were ironically rejected by his high school yearbook staff, a personal slight that would echo in the self-deprecating humor and repeated failures of Charlie Brown. These formative experiences—loss, rejection, and perseverance—gave Schulz an intuitive understanding of insecurity and self-doubt, which would become core themes in his work and set Peanuts apart as a strip of profound emotional intelligence.

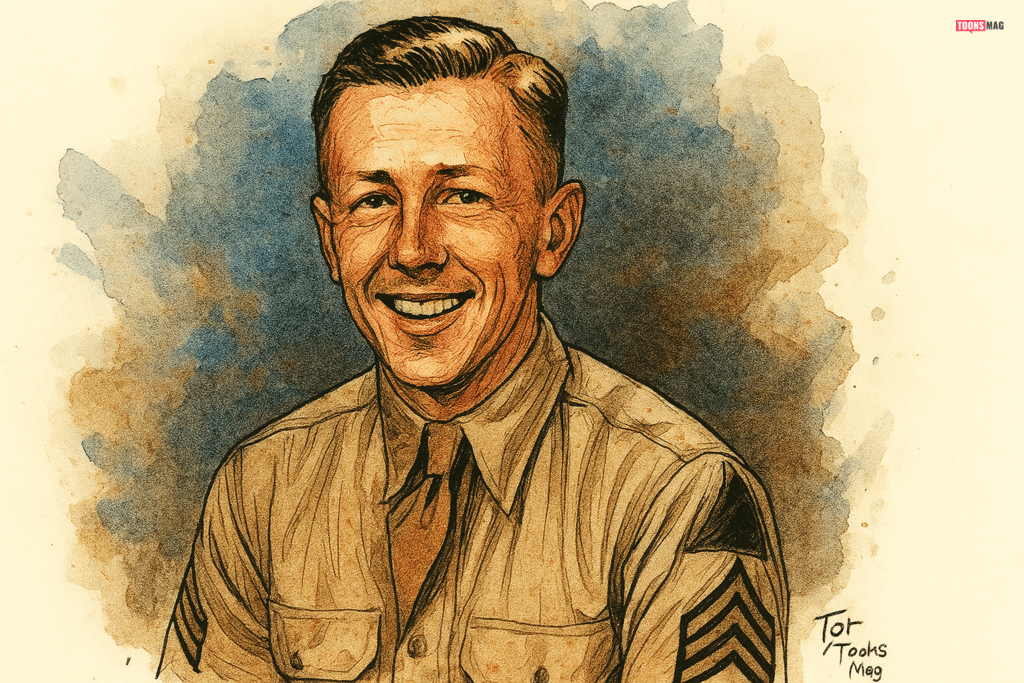

Military Service and Early Career

Schulz served in World War II as a staff sergeant with the 20th Armored Division, an experience that deeply shaped his worldview and instilled a sense of quiet resilience that would later infuse his work. He trained at Camp Campbell in Kentucky and Fort Meade in Maryland before being deployed to Europe in late 1944. He participated in combat in Germany during the final months of the war, where his division helped liberate Dachau concentration camp. Schulz earned the Combat Infantry Badge, a distinction he took pride in for the rest of his life, viewing it as a symbol of personal endurance and moral responsibility.

Although he rarely spoke at length about his military service, its psychological and ethical impact was profound. His wartime experiences would later inform the introspective nature of Peanuts, especially Snoopy’s “Flying Ace” fantasies, which served as both a humorous escape and a veiled commentary on the absurdity of war. The frequent existential pondering of characters like Charlie Brown and Linus can also be seen as rooted in Schulz’s reflections on mortality and human frailty.

Upon returning to Minnesota, Schulz resumed civilian life with a renewed sense of purpose. He worked for Timeless Topix, a Roman Catholic comic magazine, where he created content that blended moral values with visual storytelling. He later returned to Art Instruction, Inc. as an instructor, where he further honed his style and developed the professional discipline that would define his career. Schulz was known among peers for his meticulous approach to cartooning—he insisted on drawing every panel himself, a commitment that began during this early teaching phase.

His first published work, Li’l Folks, appeared in the St. Paul Pioneer Press (1947–1950). This feature included a rotating cast of characters and was distinguished by Schulz’s clear line style and understated humor. It introduced early versions of the characters who would evolve into the beloved Peanuts cast, including a precocious boy who resembled Charlie Brown and a dog not unlike Snoopy. In 1950, Schulz pitched a four-panel strip to United Feature Syndicate.

Though he wanted to retain the title Li’l Folks, the syndicate insisted on a change due to a naming conflict. They chose the name Peanuts, which Schulz detested, feeling it belittled the thoughtful content he aimed to create. Nevertheless, he agreed to proceed, driven by a vision that would soon revolutionize comic art.

The Rise of Peanuts

Peanuts debuted on October 2, 1950, in seven newspapers including the Chicago Tribune and the Washington Post. Though it began modestly, it resonated with a wide audience and grew slowly but steadily in popularity. By the mid-1960s, it had become a cultural mainstay, appearing in over 2,600 newspapers in 75 countries and translated into 21 languages. Its global reach was extraordinary, and Schulz created all 17,897 strips himself, without assistance—a rare and unmatched record in the history of syndicated comic strips.

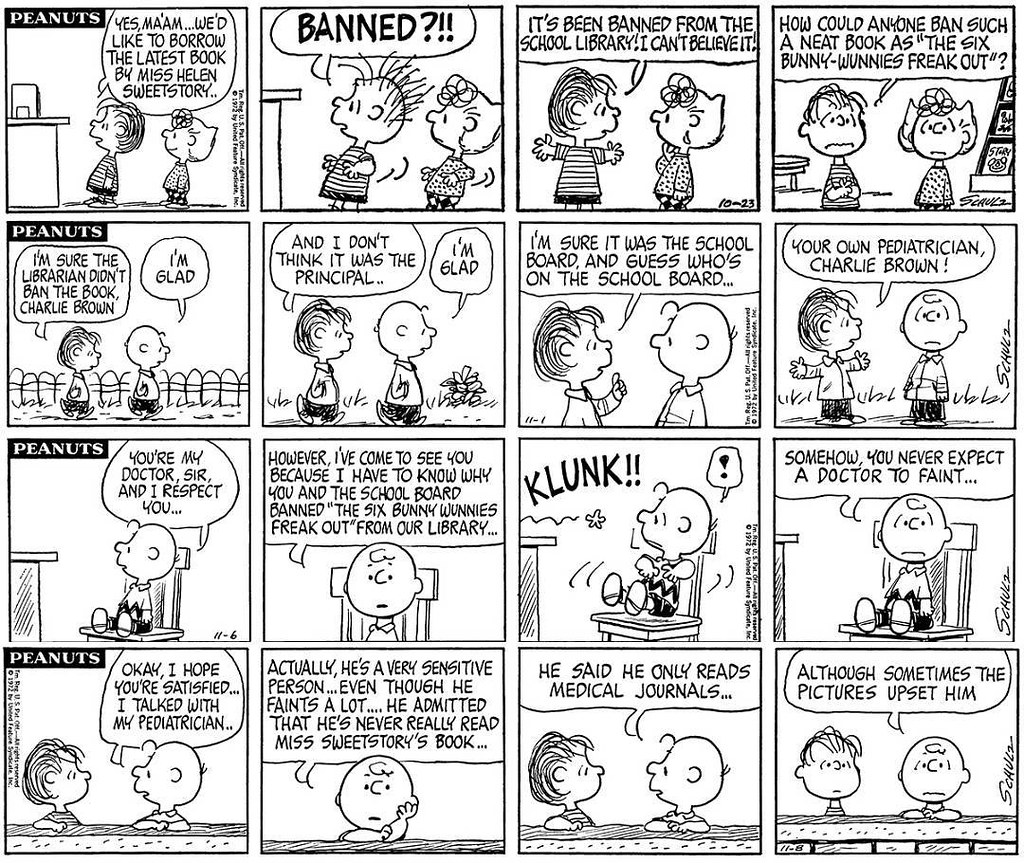

The strip introduced groundbreaking ideas for its time: philosophical and emotionally aware children who often acted as more rational beings than adults, an anthropomorphic beagle with an imagination that spanned World War I battlegrounds and literary aspirations, and a nuanced take on childhood insecurities, loneliness, and resilience. These elements turned Peanuts into more than just a comic strip; it became a lens through which readers could examine the human condition.

Characters such as Charlie Brown, Lucy, Linus, Schroeder, and Snoopy developed rich personalities and internal worlds. Charlie Brown, for example, embodied both perseverance and anxiety, a child who never won but never stopped trying. Lucy van Pelt was opinionated and forceful, yet occasionally vulnerable. Linus, the thumb-sucking philosopher with his blanket, became a voice of spiritual and ethical contemplation. Schulz drew heavily from his own experiences—his quiet Midwestern upbringing, love of baseball and classical music, personal heartbreaks, religious reflections, and existential musings.

The dialogue and scenarios in Peanuts reflected real-life challenges with poetic subtlety. The strip managed to explore complex themes—alienation, failure, ambition, and hope—while remaining accessible to readers of all ages. Its understated wit and layered symbolism invited readers to laugh, cry, and think deeply, all within the space of four minimalist panels. It established Schulz not only as a skilled cartoonist but also as a keen observer of human psychology and social dynamics.

Books, Animation, and Cultural Influence

Charles M. Schulz’s influence extended far beyond the newspaper page. His comic strip Peanuts gave rise to a massive cultural footprint through television, theater, merchandise, and publishing. With memorable animated specials, best-selling books, and iconic characters embraced across generations, Schulz’s work bridged entertainment and art, shaping the way audiences around the world engage with comics and animated storytelling.

Television and Stage Adaptations

Peanuts spawned dozens of animated TV specials, beginning with A Charlie Brown Christmas (1965), which won both an Emmy and a Peabody Award. Schulz remained deeply involved in every project, often writing or co-writing the scripts. The animated specials, such as It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown and A Charlie Brown Thanksgiving, became annual cultural traditions. These stories combined warm nostalgia with intelligent, child-centered storytelling. The strip also found life on stage with acclaimed musicals like You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown and Snoopy! The Musical, which enjoyed successful runs both off-Broadway and internationally. A 2016 Broadway revival reaffirmed the enduring appeal of Schulz’s characters and themes.

Merchandising and Licensing

From the 1950s onward, Schulz’s characters appeared on lunchboxes, greeting cards, plush toys, pajamas, and virtually every form of merchandise. Snoopy became one of the most recognizable characters in the world. By the 1990s, licensing revenues from Peanuts merchandise had topped over $1 billion annually, making it one of the most lucrative franchises in cartoon history. Partnerships with brands like Hallmark, MetLife, and countless apparel lines kept the brand visible across generations. In Japan, Snoopy’s popularity sparked Peanuts-themed cafes, museums, and even hotels. The characters continue to be global brand ambassadors, combining charm with nostalgia.

Publishing and Preservation

In addition to countless themed anthologies and children’s books, Schulz’s legacy was preserved through The Complete Peanuts project by Fantagraphics Books (2004–2016), a 26-volume collection that compiled every strip he ever drew. This comprehensive effort ensured that all of Schulz’s work would remain accessible to fans and scholars alike. The books also included introductions and commentary from prominent authors and cartoonists, further cementing Schulz’s impact on literary and artistic culture. The strip has also been archived digitally, allowing a new generation of fans to experience Schulz’s storytelling online.

Personal Life

Schulz was married twice and had five children. His first marriage to Joyce Halverson in 1951 ended in divorce in 1972, and he later married Jean Forsyth Clyde in 1973, who remained his partner until his death. His children, particularly Craig and Jill Schulz, would later become involved in preserving and promoting their father’s legacy through television and museum work. In 1958, Schulz relocated to California and settled in Santa Rosa, where he designed and built an art studio that became his creative sanctuary. The studio overlooked a redwood forest and featured large windows to let in natural light—a peaceful environment where Schulz spent countless hours drawing, writing, and reflecting.

A lifelong sports enthusiast, Schulz enjoyed baseball, tennis, and figure skating, and he was particularly passionate about ice hockey. He founded the Redwood Empire Ice Arena, also known as Snoopy’s Home Ice, which became a community hub and hosted an annual senior hockey tournament that drew participants from around the world. Schulz’s involvement in the rink was hands-on, from sponsoring teams to designing promotional art.

In his personal philosophy, Schulz explored themes of faith, ethics, loneliness, and the search for meaning—subjects that often emerged through his characters. Linus, for example, frequently voiced theological and moral questions that mirrored Schulz’s own spiritual inquiries. Although he was raised in a Lutheran household and remained religious throughout his life, Schulz’s beliefs evolved into a more contemplative, personal spirituality. His characters wrestled with dilemmas that were more than comedic setups—they were reflections of real inner conflict. These intimate connections between his life and his art gave Peanuts an autobiographical resonance rarely seen in comic strips, making Schulz’s work profoundly relatable and enduring.

Later Years and Death

In late 1999, Schulz was diagnosed with colon cancer, a revelation that shocked fans around the world. Despite his illness, he continued to work as long as he was physically able, maintaining the deeply personal connection he had with his characters and readers. As his health declined, Schulz made the difficult decision to retire, announcing that he would no longer be able to draw Peanuts, though reruns of classic strips would continue.

On February 12, 2000, Schulz passed away peacefully in his sleep at his home in Santa Rosa, California, just hours before his final Sunday strip appeared in newspapers across the globe. Fittingly, this farewell strip featured a simple yet heartfelt message of gratitude, in which Schulz thanked his readers for their decades of support. It ended with the now-iconic and emotional line: “Charlie Brown, Snoopy, Linus, Lucy… how can I ever forget them?”

His passing marked not only the end of a personal creative journey but also the close of one of the most enduring chapters in American popular culture. Tributes poured in from every corner of the world—from fellow cartoonists who cited him as a guiding influence, to fans who had grown up with his characters as companions. Newspapers published eulogies and retrospectives; television programs aired special segments honoring his legacy; and the cartooning community mourned the loss of a master whose pen captured both the whimsy and sorrow of the human spirit.

Legacy and Honors

Charles M. Schulz received numerous accolades for his groundbreaking work in the world of comics and popular culture. He was awarded the Reuben Award—considered the highest honor in American cartooning—twice, first in 1955 and again in 1964. He also won five Emmy Awards for his contributions to animated television specials and two prestigious Peabody Awards for excellence in broadcasting.

In recognition of his cultural impact, Schulz was posthumously awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in 2001, one of the highest civilian honors in the United States. Additionally, he was inducted into both the U.S. Hockey Hall of Fame and the Figure Skating Hall of Fame, acknowledging his long-standing support and promotion of winter sports through his community initiatives and personal passion.

To commemorate Schulz’s life and enduring impact, the Charles M. Schulz Museum and Research Center opened in Santa Rosa, California, in 2002. The museum serves as a major cultural destination, drawing visitors from around the world to explore original Peanuts comic strips, rare memorabilia, correspondence, and interactive exhibits that reflect Schulz’s life and philosophy. It also hosts educational programs, artist residencies, and rotating exhibitions, ensuring that Schulz’s influence continues to inspire emerging generations of cartoonists, scholars, and readers.

NASA’s Apollo 10 lunar modules were named Charlie Brown and Snoopy, reflecting the deep admiration that even astronauts held for Schulz’s work. Snoopy became an unofficial mascot for space exploration, and the Silver Snoopy Award—a prestigious commendation for NASA employees and contractors—continues to honor excellence in flight safety and mission success. Beyond space, Schulz’s legacy lives on in a variety of media: from commemorative postage stamps and statues in his hometown to tributes by fellow cartoonists in newspapers around the globe following his death. The enduring popularity of Peanuts—through reprints, animated specials, stage musicals, merchandise, and new content licensed by Schulz’s estate—has ensured that his work remains vibrant and relevant.

The Schulz Foundation, established by his family, plays a vital role in continuing his legacy. It funds educational, cultural, and artistic initiatives, particularly those that support literacy, cartooning, and community engagement. Through this foundation, Schulz’s spirit of creativity and generosity endures, echoing the values that made Peanuts such a beloved and influential force in modern storytelling.

Charles M. Schulz redefined what a comic strip could be—infusing it with humor, philosophy, and emotional realism. Through Peanuts, he offered not only a window into the joys and struggles of childhood but a profound commentary on the human experience. Schulz remains not just a cartoonist, but a visionary storyteller whose ink-on-paper insights continue to illuminate the world, one panel at a time.

This post was created with our nice and easy submission form. Create your post!

One Comment