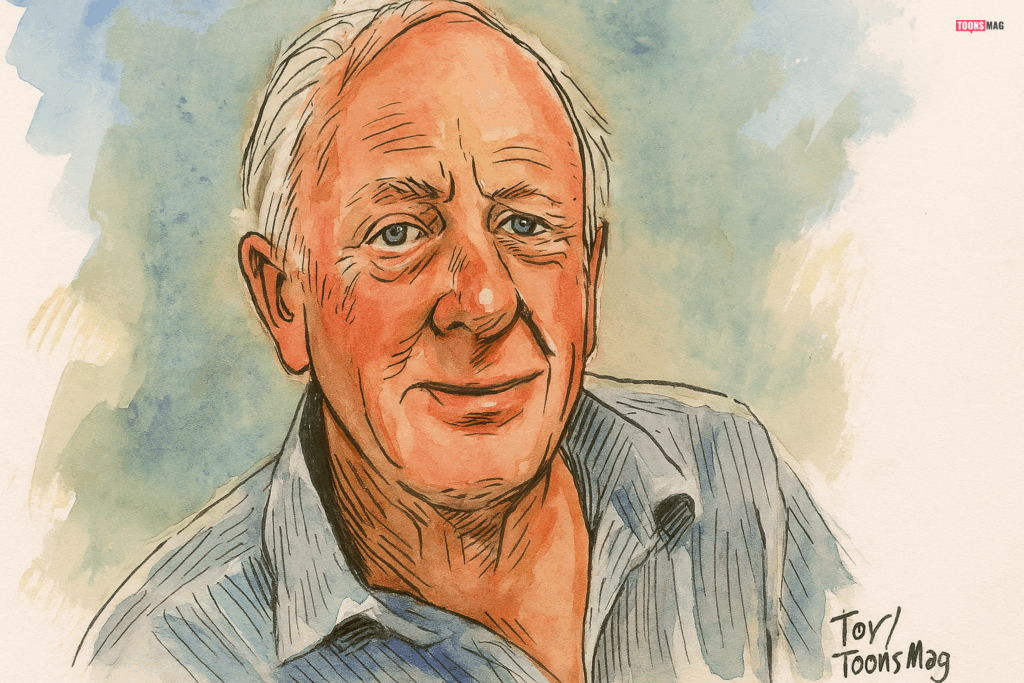

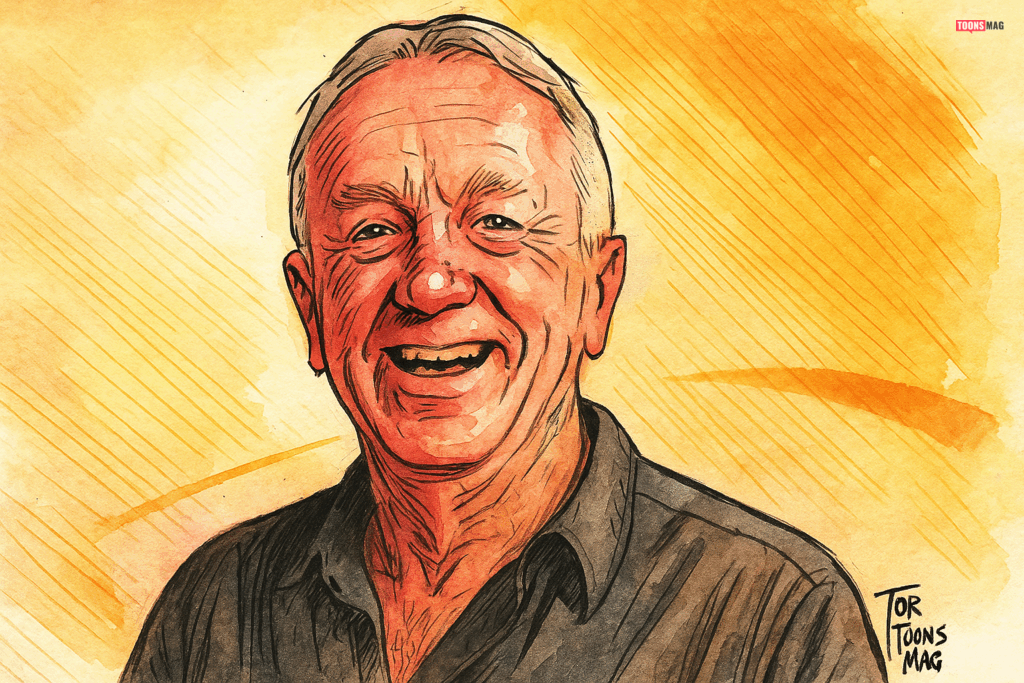

Dean Alston (born 1950) is a highly regarded Australian cartoonist and illustrator, best known for his extensive and influential career as the editorial cartoonist for The West Australian newspaper, a position he has held since 1986. Alston is celebrated for his sharp wit, bold caricatures, and incisive satirical takes on political and cultural issues in Australia. With more than four decades in media, his body of work forms a compelling visual chronicle of Western Australian and national affairs.

Infobox: Dean Alston

Name: Dean John Douglas Alston

Born: 1950

Birthplace: South Perth, Western Australia, Australia

Nationality: Australian

Occupation: Editorial cartoonist, humorist, illustrator

Years Active: 1986–present (The West Australian)

Spouse: Lisa Prendiville (m. 1984)

Children: Geraldine (Deanie), David

Known For: Editorial cartoons in The West Australian, “Alas Poor Yagan” controversy

Awards:

- Walkley Award for Best Cartoon (1991)

- Stanley Award for Best Single Gag Cartoon (2003, 2012)

- Multiple industry and state journalism commendations

Notable Works: Over 14,000 editorial cartoons, widely syndicated in Australian press

Education: Applecross Senior High School; cadetship in cartography, WA Lands and Surveys Department

Early Life and Education

Dean Alston was born in South Perth, Western Australia, in 1950. Raised in Mount Pleasant, a leafy riverside suburb nestled along the Swan River, he was exposed early to the laid-back yet culturally evolving lifestyle of Perth. This upbringing immersed him in a landscape of artistic opportunity, beach culture, and civic awareness. Alston attended Applecross Senior High School, a school known for its vibrant arts programs.

There, his early interests in drawing, storytelling, and public affairs began to converge in meaningful ways. Teachers and classmates often recall Alston doodling in the margins of his schoolbooks and illustrating impromptu satirical sketches of classroom events. His sharp wit and love of humor, coupled with a perceptive eye for detail, started to shape the distinctive observational style that would later define his career.

In 1967, at the age of 17, he began a cadetship in cartography with the Western Australia’s Lands and Surveys Department. This position required technical precision and an acute sense of spatial orientation, both of which played a pivotal role in honing his draftsmanship. The job entailed creating detailed maps of vast and often remote regions of Western Australia, exposing Alston to the region’s diverse geography, historical topography, and evolving infrastructural changes. Through this work, he developed a meticulous approach to line work, a trait that would carry over into his cartoons.

His exposure to regional culture, land disputes, and the bureaucratic mechanisms of state planning during this time planted the seeds for his future political awareness and satirical edge. This experience not only gave him a solid technical foundation but also deepened his appreciation for the visual language of place—something that frequently appears in his depictions of Western Australian identity.

Diverse Career Path and Overseas Adventures

Before fully immersing himself in the world of illustration and editorial satire, Alston explored a variety of vocations, each of which contributed to the mosaic of experiences that would inform his later cartooning career. In 1980, he made a bold entrepreneurial move by buying into the Carine Glades Tavern, a popular northern suburbs venue, where he served as manager until 1984.

This role demanded not only business acumen but also honed his keen observational skills, as he dealt daily with a diverse clientele ranging from working-class patrons to local politicians and artists. Alston has often credited this period with refining his sense of timing and humor, especially as it relates to reading social cues and understanding audience psychology—critical tools for a successful satirist.

In 1984, Alston married Lisa Prendiville, a spirited and supportive partner who played a stabilizing role in his creative life. Soon after, they embarked on an adventurous eighteen-month stint in England, an experience that would prove pivotal both personally and professionally. The couple welcomed their daughter Geraldine (“Deanie”) in 1985 and later their son David in 1988, anchoring their lives amid rapid change.

During their time abroad, Alston wore many hats with characteristic enthusiasm: he worked as a bus driver, which gave him a grassroots view of British society; a cartographer and illustrator for British Gas, where he merged technical drawing with visual storytelling; and a comic strip artist for a news and travel magazine, producing whimsical, culturally attuned content for an international readership.

He also visited numerous art museums and public exhibitions, soaking in the rich history of European cartooning—from the satire of Punch magazine to contemporary graphic art. These roles and encounters broadened his creative repertoire, refined his artistic style, and deepened his appreciation for multiculturalism and global perspectives—threads that would subtly but powerfully appear in his later editorial work back in Australia.

Rise as an Editorial Cartoonist

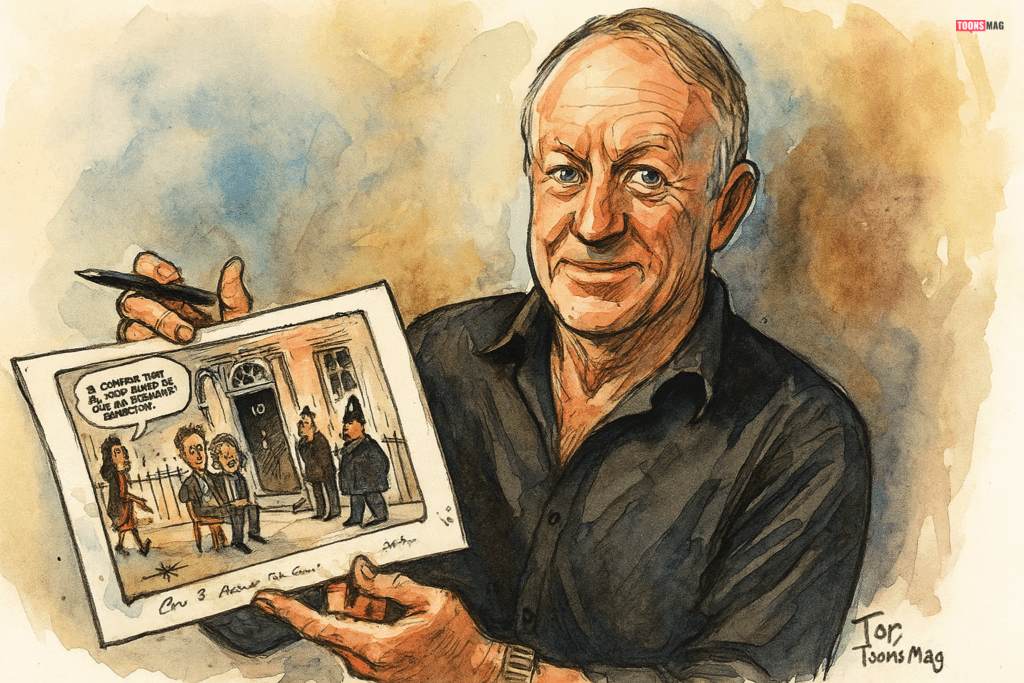

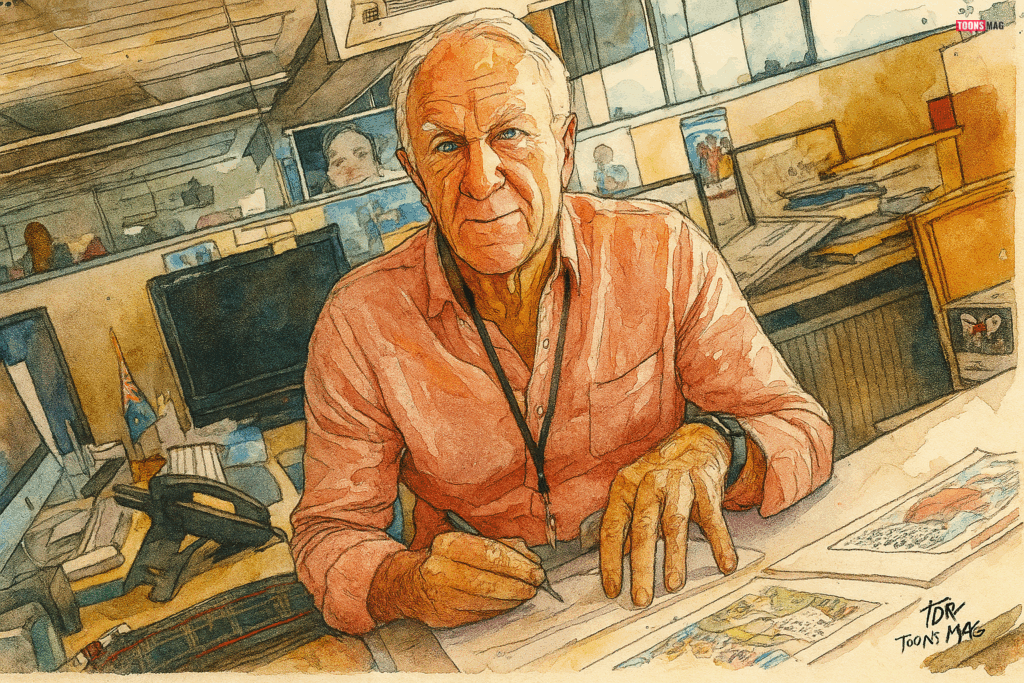

Upon returning to Western Australia in 1985, Alston joined The West Australian, initially contributing illustrations and spot cartoons for feature stories and editorials. His incisive and timely drawings quickly gained popularity, and within a year, he succeeded Peter Clarke as the new editorial cartoonist. His appointment marked the beginning of a remarkably prolific chapter in Australian media, one that would span decades and shape the visual identity of political discourse in Western Australia.

Alston quickly became known for his fearless political commentary, technical proficiency, and humorous engagement with everyday readers. He developed a distinct style that combined detailed linework with expressive caricature, and his ability to distill complex issues into compelling visual narratives made him a fixture of the paper’s editorial voice. His cartoons often juxtaposed biting satire with local humor, resonating with audiences across political and cultural spectrums.

By 2005, Alston had published close to 10,000 cartoons, and by 2016, that number had surpassed 14,000—a testament to his enduring commitment and creative stamina. He was especially prolific during election cycles, where his pointed takes on political candidates and public policy drew widespread attention. His editorial cartoons typically merge local and national political issues, characteristically rendered with exaggerated facial features, dramatic visual metaphors, and densely layered compositions that reward close scrutiny. His style includes recurring themes, visual in-jokes, and cultural references ranging from sports and opera to local folklore, often delighting readers who catch these subtle cues.

In addition to topical political satire, Alston frequently addressed broader cultural themes such as environmental conservation, urban development, and societal attitudes toward immigration and diversity. His nuanced portrayals often prompted public discussion, with some cartoons even sparking responses in letters to the editor columns and radio call-in shows.

Alston has received multiple accolades for his work:

- 1991 Walkley Award for Best Cartoon — Australia’s premier journalism prize

- Stanley Award for Best Single Gag Cartoon in 2003 and 2012, presented by the Australian Cartoonists Association

- Numerous state and industry commendations celebrating his contributions to political discourse, satirical journalism, and media arts

Personal Traits and Artistic Environment

Known around The West newsroom for his booming laugh, quick wit, and irreverent charm, Alston is a personality as colorful as his cartoons. He’s deeply passionate about history, particularly that of Scotland, where his family heritage lies. He is an enthusiastic supporter of the arts and maintains a private collection of historical memorabilia, cartoons, vintage illustrations, and rare satirical prints from the 18th and 19th centuries, which he has collected during his travels across Europe and North America.

Despite the sedentary nature of cartooning, Alston is physically active and values maintaining his fitness. He engages in gym sessions, surf skiing, open water swimming, and sand running—all of which help him manage the physical demands of daily cartoon production while staying mentally alert. He often jokes that staying fit is not just about health but about “outpacing deadlines.” He has been known to lament his aging knees and the occasional sore wrist from years of inking, though never his enthusiasm.

His workspace is a chaotic yet creative haven: strewn with folders of original drawings, sketches pinned to corkboards, figurines (including a Lancaster bomber and Buzz Lightyear), and an old leather jacket bought from a London market in the 1980s. The room also includes model airplanes, vintage cartoon books, and a well-used drawing table covered in ink stains and coffee rings. The office houses scrap paper caricatures of colleagues created during friendly banter, usually after the phrase: “I’m going to get you for that!” Some of these caricatures have become iconic within the newsroom, even being framed and displayed by amused coworkers.

The “Alas Poor Yagan” Controversy

In September 1997, Alston ignited widespread national controversy with his cartoon titled “Alas Poor Yagan”, which commented on the divisive debates surrounding the repatriation of Yagan’s head, a revered Noongar leader and significant cultural figure. Yagan’s remains had been returned to Australia from the United Kingdom after over a century, and the event was expected to be one of solemn unification. However, the process instead exposed internal disagreements among Indigenous groups about who had the authority to receive and represent Yagan’s legacy. Alston’s cartoon sought to highlight this disunity, but many readers interpreted it differently.

The cartoon included caricatures and references to named Noongar individuals, some of whom were depicted with exaggerated features or presented in ways that critics said mocked Indigenous heritage and spiritual beliefs. Among those outraged was Aboriginal elder Robert Bropho, who vocally condemned the cartoon as racist, culturally disrespectful, and deeply offensive to the Noongar people. The backlash was swift and significant, prompting public outcry and a formal complaint to the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission.

After a thorough review, the Commission concluded that although the cartoon was offensive and insensitive, it did not constitute a violation of the Racial Discrimination Act, as it did not incite hatred or perpetuate discriminatory acts. Dissatisfied with the outcome, Bropho and his supporters appealed the decision, but the Federal Court of Australia ultimately upheld the Commission’s ruling. The decision further inflamed debate about the boundaries of artistic expression and satire, especially in matters involving race, history, and cultural sensitivity.

Alston defended his intentions, asserting that the cartoon was aimed at critiquing intra-community conflict and highlighting political fragmentation, not at disparaging Indigenous identity or belief systems. Nevertheless, the controversy remains a landmark case in Australian media ethics, frequently studied in journalism and law curricula. It underscores the challenges faced by editorial cartoonists in navigating the fine line between satire and offense, and the broader societal responsibilities of the press in representing culturally sensitive issues.

Legacy, Mentorship, and Continuing Impact

Alston continues to produce daily editorial cartoons for The West Australian and contributes to PerthNow, The Sunday Times, and a range of syndicated news services and periodicals across Australia. His consistent output provides readers with not only a sharp, humorous take on political events but also a running visual commentary on the absurdities, hypocrisies, and peculiarities of modern life, governance, and societal norms. His cartoons are widely shared online and have been exhibited in multiple retrospectives celebrating Australian cartooning traditions.

Beyond his published work, Alston is an active and generous mentor within both the artistic and journalistic communities. He has guest lectured at universities such as Curtin University and the University of Western Australia, offering masterclasses in visual satire and editorial commentary. He has served as a judge and keynote speaker at events including the Stanley Awards, and contributed to panel discussions on the evolving role of political satire in an age of digital misinformation.

Alston’s contributions extend to public exhibitions and traveling retrospectives, where his cartoons are celebrated not only as journalistic records but also as dynamic cultural artifacts that document the shifting contours of public opinion. He is also a frequent contributor to community art initiatives, school workshops, and local satire festivals such as the Fremantle Street Arts Festival, where he advocates for arts education and the preservation of visual satire.

Continuing to influence younger generations of illustrators, Alston is renowned for his balanced blend of humor, critique, and artistic dedication. Many consider him a custodian of Western Australia’s political memory, having sketched nearly every major political figure and public scandal in the state over the past 40 years, with uncanny accuracy and fearless flair.

His legacy is marked by his fearlessness, creative rigor, and an unrelenting drive to use humor and visual storytelling as lenses through which Australians see themselves, their leaders, and their evolving national identity. His daily cartoons remain both a mirror and a magnifying glass for Australian society—illuminating, satirizing, and, at times, provocatively challenging the status quo.

This post was created with our nice and easy submission form. Create your post!