Tintin (/ˈtɪntɪn/; French: [tɛ̃tɛ̃]) is the titular hero of The Adventures of Tintin, a landmark comic book series created by Belgian cartoonist Hergé (Georges Remi) in 1929. Debuting in the youth supplement Le Petit Vingtième of the conservative Belgian newspaper Le Vingtième Siècle, Tintin made his first appearance in Tintin in the Land of the Soviets. The character—portrayed as an intrepid young reporter with a sharp intellect, strong moral compass, and trusty fox terrier Snowy—rapidly grew into one of the most recognized and beloved figures in European comics, defining the genre’s golden age.

Infobox: Tintin

Character Name: Tintin

Created By: Georges Remi (Hergé)

First Appearance: Tintin in the Land of the Soviets (1929)

Species: Human

Occupation: Reporter, Detective, Explorer

Nationality: Belgian

Known For: Journalism, Adventure, Investigative Skills, Moral Integrity

Companion: Snowy (Milou) – White Wire Fox Terrier

Recurring Allies: Captain Haddock, Professor Calculus, Thomson and Thompson

Total Comic Albums: 24 (+1 unfinished)

Language of Origin: French

Main Publisher: Casterman (Belgium)

Translations: Over 70 languages

Total Copies Sold: Over 200 million

Film Adaptation: The Adventures of Tintin (2011), directed by Steven Spielberg

Museum: Musée Hergé, Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium

A Global Literary and Cultural Phenomenon

Tintin’s appeal quickly transcended Belgium, resonating with audiences across Europe and eventually worldwide. The universality of his character—a courageous, ethical, and resourceful young man—allowed readers of diverse backgrounds and cultures to identify with him. Over the decades, Tintin has evolved into a global icon representing adventure, curiosity, and justice. His clean design, clear moral code, and international escapades provided both entertainment and subtle lessons on integrity, resilience, and global citizenship.

Each album follows him on high-stakes missions set in a wide variety of locales—ranging from the political upheaval in South America and secret cults in the Indian subcontinent to hidden treasures in the Caribbean and even lunar exploration long before the Moon landing. These narratives not only entertained but also introduced young readers to distant cultures, geopolitical conflicts, and ethical dilemmas. His allies, including the ever-irascible Captain Haddock, the eccentric genius Professor Calculus, and the bumbling detectives Thomson and Thompson, contributed essential comic relief, philosophical nuance, and deepened emotional engagement. Their inclusion helped establish a dynamic and multi-dimensional cast that remains fresh and engaging to this day.

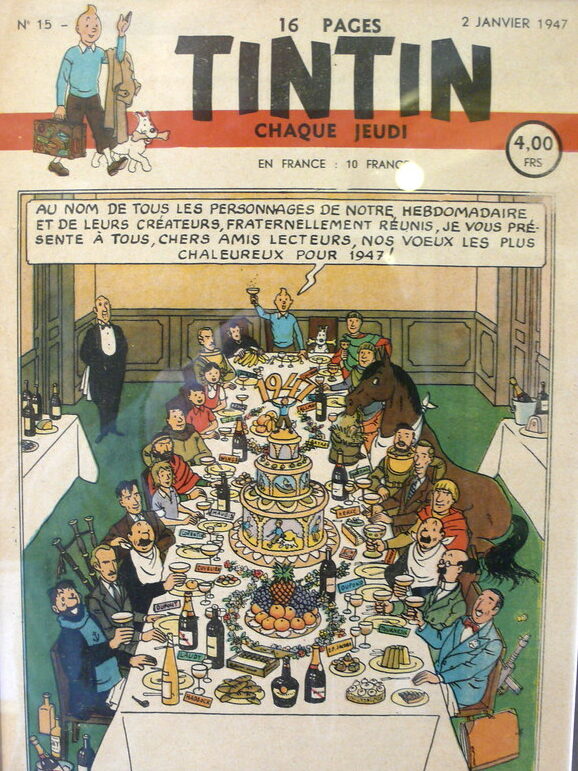

Tintin’s global popularity is reflected in his omnipresence in bookstores, academic curricula, pop culture references, and multilingual publishing. Cultural festivals from Angoulême in France to Comic Con events across the globe feature Tintin prominently. Countless exhibitions, themed cafés, public statues, murals, and even metro stations across Europe and beyond celebrate his artistic and cultural significance. His adventures are also widely used in educational contexts—from teaching storytelling and visual literacy to promoting language acquisition and intercultural understanding. Today, Tintin continues to bridge generations, offering both nostalgic appeal to older readers and fresh excitement to new ones.

International Reach and Public Domain Status

With over 200 million copies sold and translations into more than 70 languages, The Adventures of Tintin has had an extraordinary cultural impact that transcends national borders and generations. First released as serialized comic strips in a Belgian Catholic newspaper, the series quickly evolved into a global publishing phenomenon. Its mix of thrilling storytelling, morally anchored characters, and culturally rich backdrops allowed it to gain traction across diverse regions—from postwar Europe to Asia, Latin America, and Africa.

Beyond print, the series has been adapted into multiple media forms, including mid-century live-action films, radio plays, an influential 1990s animated television series, stage productions, and the critically acclaimed 2011 film The Adventures of Tintin, directed by Steven Spielberg and produced by Peter Jackson. These adaptations not only revived interest in the original albums but also introduced the world of Tintin to new audiences raised in the digital era. The Spielberg film, with its cutting-edge motion capture and nostalgic fidelity to Hergé’s vision, was particularly successful in rejuvenating interest among younger generations.

In addition to entertainment, Tintin has entered the realm of education, where his adventures are used to teach languages, geography, and critical thinking. Scholars and educators alike often reference Tintin when illustrating historical conflicts, colonial critique, and evolving cultural norms in the 20th century. His narratives are regularly included in comparative literature courses and comic studies curricula.

As of January 1, 2025, the earliest Tintin stories, starting with the original 1929 French publications, have entered the public domain in the United States, allowing for unrestricted republication and adaptation by educators, publishers, and creators. This status change enables the stories to be reimagined or repurposed in academic settings, open-source projects, or creative reinterpretations. Each subsequent year, additional Tintin works will become part of the public domain in the U.S., unless copyright laws are extended. However, the series remains under copyright protection in Belgium and other countries with legislation based on the author’s lifetime plus 70 years rule, meaning that the entire Tintin catalog will remain copyrighted in many parts of the world until at least 2054.

This dual status—public domain in some jurisdictions, copyrighted in others—adds complexity to how Tintin is distributed and celebrated globally. It also raises fascinating legal and ethical questions about creative reuse and cultural heritage in a transnational media landscape.

Origin and Inspiration

Hergé drew inspiration from a variety of sources while developing Tintin. A central figure in this creative process was his younger brother Paul Remi, whose physical appearance, military-style posture, and mischievous energy provided the visual and behavioral blueprint for Tintin. Paul’s role as a soldier and his real-life exploits significantly influenced Tintin’s demeanor and bravery. Hergé’s earlier creation, Totor, a resourceful Boy Scout character featured in Le Boy Scout Belge, laid the groundwork for Tintin’s morally upright, practical, and adventurous personality. Totor’s scouting values—honesty, resilience, and global curiosity—were seamlessly carried over to Tintin.

Real-world adventurers and journalists also served as models for the character. Among them was Palle Huld, a Danish teenager who traveled the globe in 44 days in 1928 as part of a contest celebrating Jules Verne’s legacy, and shared his journey in serialized reports—an experience closely paralleling Tintin’s early globe-trotting exploits. Hergé was deeply influenced by pioneering investigative journalists such as Albert Londres, whose fearless pursuit of truth and exposés on international injustices helped shape the archetype of the crusading reporter. Hergé admired Londres’s ability to navigate complex global issues with clarity and integrity.

Literary inspirations included Rouletabille, the brilliant young sleuth from Gaston Leroux’s detective novels, whose rational thinking and moral compass foreshadowed Tintin’s detective-like qualities. The animal artistry of Benjamin Rabier also played a crucial role, especially in shaping the lively and expressive behavior of Snowy. Rabier’s flair for giving animals personality through facial expression and posture directly influenced how Hergé rendered Snowy as more than just a sidekick—he became a humorous, intelligent, and sometimes even sarcastic co-protagonist.

In addition, Hergé’s Catholic upbringing and exposure to colonial propaganda, combined with his later disillusionment with such ideologies, informed the evolving ethical and political dimensions of Tintin’s character. As Hergé matured, so too did Tintin—shifting from a naive propagandist figure into a deeply conscientious and globally aware traveler who embodies empathy, justice, and intellectual curiosity.

Early Development

Tintin was born on January 10, 1929, in the first serialized episode of Tintin in the Land of the Soviets. This initial adventure—deeply rooted in the anti-communist ideology of the conservative Catholic newspaper Le Vingtième Siècle—portrayed the Soviet Union in stark, propagandistic tones, aligning with the paper’s editorial stance. Hergé, then a young illustrator, initially relied on secondary sources and ideologically motivated reports to construct Tintin’s world. Despite these early limitations, the comic resonated with readers, establishing Tintin as a bold, adventurous figure willing to expose hidden truths in dangerous political environments.

Over time, the series evolved dramatically, breaking free from its ideological origins. As Hergé matured artistically and intellectually, so too did his creation. The early simplicity of Tintin’s character gave way to complex narratives rich in symbolism, nuance, and ethical reflection. With each subsequent album, Hergé displayed greater narrative sophistication, often addressing themes of friendship, betrayal, colonialism, and intercultural understanding. Albums like The Blue Lotus, The Calculus Affair, and Tintin in Tibet showcased a distinct shift toward moral introspection and geopolitical awareness, underscoring Tintin’s transformation from a propaganda figure to a global symbol of empathy and truth-seeking.

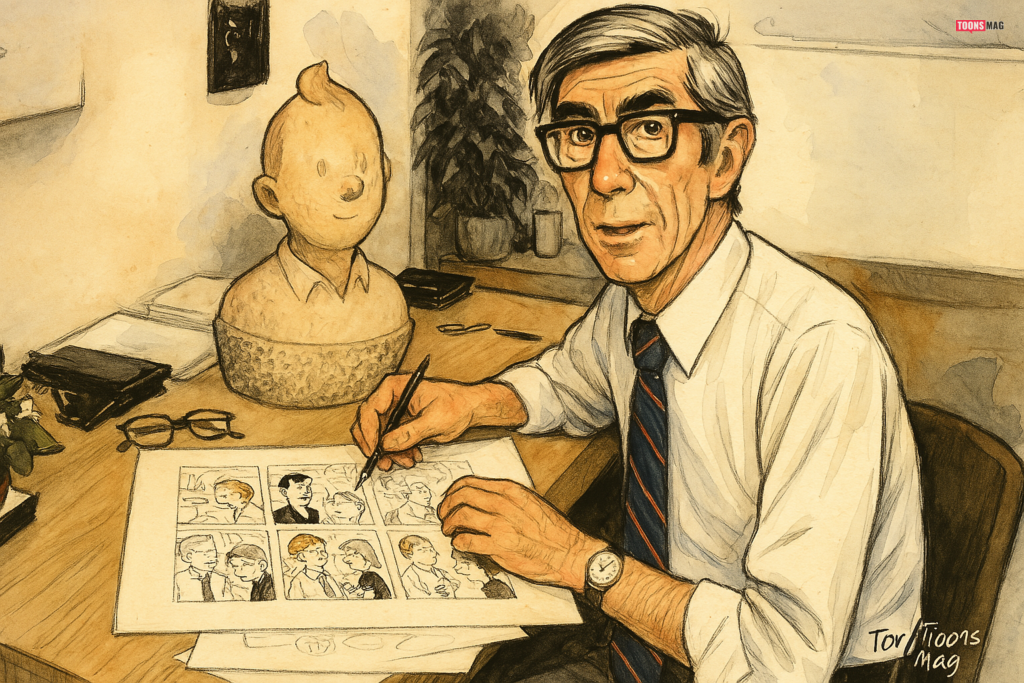

The founding of Studios Hergé in 1950 marked a pivotal milestone in the series’ development. This professionalization allowed Hergé to delegate time-consuming tasks to a carefully selected team of collaborators, which in turn freed him to focus on narrative structure and artistic direction. Under the studio model, backgrounds became more detailed, props and locations more accurate, and character interactions more layered. Assistants conducted extensive visual and cultural research, using photographs, maps, scientific data, and architectural references to give Tintin’s world a striking sense of realism.

One of the most influential contributors was Chinese artist Zhang Chongren, whom Hergé befriended during his work on The Blue Lotus. Zhang, a student at Brussels’ Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts, not only introduced Hergé to Chinese language and art but also educated him about the socio-political complexities of China and its resistance to imperialism. As a result, The Blue Lotus abandoned earlier racial stereotypes and marked a dramatic pivot in Hergé’s worldview. The album was praised for its accurate cultural depiction and its condemnation of Western colonial arrogance. Zhang’s contribution represents a turning point in the Tintin saga, setting a precedent for the meticulous cultural sensitivity and realism that would define Hergé’s later work.

Iconic Imagery and Personality

Visually, Tintin became an instantly recognizable symbol of European comics. His signature quiff, round face, plus fours, and blue sweater became iconic in popular culture. Hergé deliberately crafted this minimalist design to ensure that Tintin remained approachable and timeless, allowing readers of all ages to project themselves onto the character. Tintin’s age is deliberately ambiguous, with Hergé placing him somewhere between adolescence and early adulthood—a timeless adventurer immune to the passing of years. His appearance changed little over the series’ 50-year run, maintaining continuity and charm, which in turn solidified his iconic visual identity. Even his expressive body language was meticulously designed to transcend language barriers, helping the character gain universal appeal.

Tintin’s skills are vast and often surprising, crafted to reflect the Renaissance ideal of a virtuous, multi-talented hero. He demonstrates mastery in driving, piloting various aircraft, sailing ships, swimming long distances, and even operating advanced spacecraft—well before the space age captivated public imagination. He’s also proficient in foreign languages, Morse code, first aid, marksmanship, martial arts, and disguise. These capabilities, while occasionally exaggerated for narrative effect, emphasize the Boy Scout virtues that Hergé held dear—resourcefulness, discipline, loyalty, and altruism. His ability to blend into different cultures, communicate with diverse people, and maintain composure under pressure reinforces his role as a humanitarian adventurer.

Tintin’s skills aren’t merely physical; he exhibits keen investigative acumen, frequently piecing together complex geopolitical puzzles and criminal conspiracies with logic and intuition. He maintains moral clarity in ambiguous situations, often risking his life for truth and justice. Critics like Pierre Assouline have observed that Tintin is emotionally neutral, functioning as a narrative mirror in which readers see themselves. This allows for a broader emotional connection across cultural and generational lines. Others like Michael Farr have emphasized his unwavering ethics, universal relatability, and the balance of courage and humility that defines his character. Hergé once noted that Tintin was the boy he had always wanted to be—upright, intelligent, and brave.

Literary Criticism and Tintinology

The academic study of Tintin, often referred to as Tintinology, has produced a rich body of literature exploring Hergé’s methods, motifs, and long-lasting impact on the world of comics and beyond. Writers such as Philippe Goddin, Benoît Peeters, and Harry Thompson have authored in-depth biographies and critical analyses that delve into Hergé’s storytelling techniques, artistic innovations, and philosophical evolution. Their work dissects Tintin’s narrative architecture, psychological depth, intertextual references, and complex socio-political undertones—ranging from colonial discourse to anti-totalitarianism.

Academic interest extends to the ligne claire art style, pioneered by Hergé, which emphasizes clean lines, bright colors, uniform line thickness, and realistic yet stylized backgrounds. Scholars have noted that this style enabled Hergé to blend simplicity with sophistication, making the stories accessible to children while retaining enough visual and thematic complexity for adult readers. This visual clarity, combined with Tintin’s emotionally neutral personality, allows readers to project themselves onto the protagonist and immerse themselves in complex stories that balance fast-paced adventure with nuanced satire and moral reflection.

The result is a layered literary experience that continues to attract scholarly attention from diverse academic disciplines. In literature, scholars have examined Tintin’s narrative structure, character development, and mythological motifs. In history, researchers have contextualized Tintin’s adventures within real-world conflicts such as the Sino-Japanese War, the Cold War, and European colonialism. Post-colonial studies often interrogate Hergé’s early depictions of non-European cultures while acknowledging his significant growth in sensitivity and representation. Semiotics experts analyze the recurring symbols and coded language throughout the series, while sociologists and psychologists explore Tintin’s enduring appeal and identity as a universal moral agent.

Universities in Belgium, France, the UK, and North America have incorporated Tintin studies into courses on comics theory, European cultural history, and media literacy. Conferences and symposia dedicated to Hergé and Tintin continue to explore new dimensions of the work, ensuring its place not only as popular entertainment but as a respected subject of literary and visual analysis.

Controversies and Cultural Evolution

While widely praised, the Tintin series has also been the subject of critical reevaluation, particularly in relation to its early portrayals of race, empire, and cultural superiority. Volumes such as Tintin in the Congo and Tintin in America have been condemned for their overtly stereotypical depictions of African and Native American characters, often portrayed with exaggerated physical features and subordinate roles. Critics have noted that these depictions reflected the Eurocentric, colonialist mindset prevalent in 1930s Europe and contributed to the normalization of racial hierarchies and cultural misrepresentation in popular media.

These issues sparked debate not only among literary scholars and postcolonial critics but also in wider cultural discourse, with calls for removal or censorship of certain albums from school libraries and public collections. In response, publishers began including explanatory prefaces in newer editions of controversial titles, acknowledging the historical context and encouraging critical engagement rather than passive consumption. Such additions aim to educate readers on the evolution of societal values and the importance of viewing cultural products through a historical lens.

Hergé himself expressed regret over these early depictions. As his awareness and worldview matured, particularly after his friendship with Chinese artist Zhang Chongren, he made a decisive shift in tone and substance. The Blue Lotus represented a major pivot: it portrayed Chinese characters with depth and dignity, challenged Western imperialism, and included accurate cultural references based on firsthand input. This sensitivity deepened in subsequent albums such as The Red Sea Sharks, which criticized the slave trade, and Tintin in Tibet, a poignant story rooted in loyalty, pacifism, and spiritual reflection.

By the 1960s and 70s, Hergé was actively revising earlier works, removing or altering problematic content. These changes—ranging from visual edits to narrative restructuring—highlight his willingness to adapt and atone. The overall trajectory of the series thus mirrors Hergé’s personal growth: a journey from colonial complacency to cosmopolitan empathy. Today, Tintin is frequently cited in discussions about how historical media can serve as both cultural artifact and tool for ethical reflection in an increasingly globalized world.

Final Years and Tintin’s Legacy

Hergé died in 1983 from leukemia, leaving behind the incomplete Tintin and Alph-Art, a surreal story centered around the world of modern art, counterfeit art galleries, and philosophical musings on authenticity. Although Hergé had produced substantial rough sketches, dialogue outlines, and plot notes, the album was never fully realized. In keeping with Hergé’s explicit instructions, no new Tintin adventures were permitted to be created by other artists after his death.

He firmly believed that Tintin was inseparable from his own creative vision and feared dilution of the character’s integrity through commercialization or reinterpretation. Nevertheless, Alph-Art was posthumously published in 1986 in its raw, unfinished form. Scholars and fans alike have since studied it closely, analyzing the surrealist direction and thematic depth that suggested a new phase in Hergé’s storytelling, potentially darker and more introspective than prior albums.

Tintin’s legacy today is carefully protected and promoted by the Hergé Foundation, officially rebranded as TintinImaginatio. This organization manages the intellectual property of the Tintin universe, curates global exhibitions, and collaborates with publishers, filmmakers, educators, and fashion designers to maintain Tintin’s presence in contemporary culture. One of its most enduring achievements is the Musée Hergé in Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium, a state-of-the-art institution that attracts thousands of visitors annually. The museum is not only a shrine to Hergé’s artistic brilliance but also a research center, housing archives, original sketches, manuscripts, and correspondence that shed light on the creative evolution of Tintin.

Internationally, Tintin continues to inspire multiple generations. His stories are included in literary and visual culture curricula in universities around the world, from courses on European comic traditions to seminars on intercultural dialogue and ethics in popular media. Museum retrospectives often include panels from Tintin alongside commentary on colonialism, artistic style, and narrative structure. In recent years, Tintin has made appearances in fashion lines, animated short films, NFT art projects, and even augmented reality museum experiences. National tributes also continue: in 2024, Adidas designed a new away jersey for the Belgian national football team inspired by Tintin’s iconic blue sweater and plus fours—a blend of nostalgia and national pride.

Whether through his relentless pursuit of truth, unwavering moral compass, or capacity to transcend linguistic and cultural barriers, Tintin endures as a global cultural touchstone. He stands as not only a symbol of the golden age of European comics but also a mirror of the human spirit—resilient, curious, and compassionate—echoing across time as an enduring beacon of imagination and ethical storytelling.

One Comment