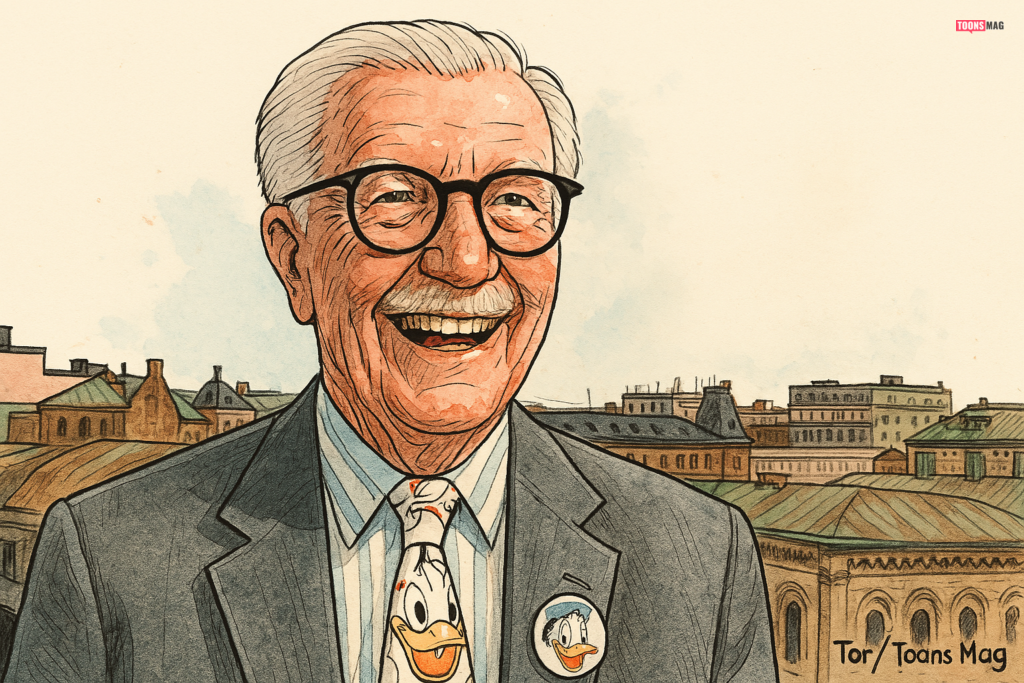

Carl Barks (March 27, 1901 – August 25, 2000) was an American cartoonist, writer, and painter whose Donald Duck and Uncle Scrooge comic-book stories for Disney/Western Publishing set the gold standard for humor‑adventure storytelling. Working anonymously for decades—fans nicknamed him “The Good Duck Artist”—Barks created Duckburg and many of its inhabitants, including Scrooge McDuck (1947), Gladstone Gander (1948), the Beagle Boys (1951), The Junior Woodchucks (1951), Gyro Gearloose (1952), Cornelius Coot (1952), Flintheart Glomgold (1956), John D. Rockerduck (1961), and Magica De Spell (1961). In 1987 he was among the first inductees of the Will Eisner Comic Book Hall of Fame.

Animation historian Leonard Maltin called Barks “the most popular and widely read artist‑writer in the world,” while Will Eisner dubbed him “the Hans Christian Andersen of comic books.”

Infobox: Carl Barks

| Born | March 27, 1901 — near Merrill, Oregon, U.S. |

| Died | August 25, 2000 (aged 99), Grants Pass, Oregon, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupations | Cartoonist, writer, painter, inker, letterer |

| Known for | Donald Duck & Uncle Scrooge stories; creation of Duckburg cast |

| Notable creations | Scrooge McDuck; Junior Woodchucks; Gyro Gearloose; Beagle Boys; Gladstone Gander; Magica De Spell; Flintheart Glomgold; John D. Rockerduck; Cornelius Coot; Neighbor J. Jones; Glittering Goldie |

| Spouses | Pearl Turner (m. 1923; div. 1929); Clara Balken (m. 1932; div. 1951); Garé Williams (m. 1954; d. 1993) |

| Children | 2 |

| Also known as | “The Duck Man,” “The Good Duck Artist” |

Overview & Legacy

Barks fused slapstick with globe‑trotting adventure and beautifully staged backgrounds, crafting stories that read with cinematic momentum. His work inspired generations of readers and creators; the DuckTales TV series (1987 and its 2017 reboot) drew heavily on his characters and plots. Outside comics, filmmakers like Steven Spielberg and George Lucas acknowledged Barks’s treasure‑hunt set pieces as inspiration.

Early Life (1901–1918)

Raised on farms in Oregon and later California, Barks experienced an isolated and rural upbringing characterized by long walks to a one‑room schoolhouse, heavy farm chores such as milking cows, feeding livestock, and harvesting crops, and very few playmates his own age. The family’s modest means and the remoteness of their homesteads meant that books, newspapers, and his own imagination were among his chief companions.

By 1916, tragedy struck when his mother died, and his worsening hearing—partly due to repeated untreated ear infections—made regular high school attendance impractical. He left formal education to work in various manual and odd jobs, an early immersion in the hardships and resilience of working people that would later inform his comics’ empathy for strivers, his portrayals of self‑reliance, and his wry, sometimes bittersweet view of fate.

From Job to Job (1918–1935)

In his teens and 20s, Barks cycled through an array of physically demanding and hands‑on jobs—farmer, woodcutter, mule driver, printer, ranch hand, and even short‑term construction laborer—while persistently teaching himself the craft of cartooning during evenings and spare moments. He briefly enrolled in correspondence art courses, which gave him exposure to professional techniques and critique. Around this time, he began successfully selling single‑panel gag cartoons and humorous illustrations to magazines such as Judge and the risqué Calgary Eye‑Opener, where his work ranged from mild satire to bawdy humor.

His contributions to the Eye‑Opener became so valued that he eventually edited and drew much of the magazine, refining his skills in pacing, composition, and audience engagement. In his personal life, he married Pearl Turner in 1923, with whom he had two daughters before divorcing in 1930, and later wed Clara Balken in 1932, balancing domestic life with his growing aspirations as a professional cartoonist.

Disney Story Department (1935–1942)

Hired by Walt Disney Studios in late 1935, Barks started as an inbetweener, then moved into story. He contributed gags and storyboards to many classic Donald Duck shorts—among them Donald’s Nephews (1938), Mr. Duck Steps Out (1940), Timber (1941), The Vanishing Private (1942), and The Plastics Inventor (1944 concept). The move honed his timing and visual clarity.

Allergic to the studio’s air conditioning and unhappy with wartime strains, he left Disney in 1942. Before departing he co‑drew (with Jack Hannah) the pioneering comic Donald Duck Finds Pirate Gold (Dell Four Color #9, 1942), launching a treasure‑hunt theme he would revisit often.

Western Publishing & The Good Duck Artist (1943–1966)

Relocating to the Inland Empire east of Los Angeles, Barks initially planned to operate a chicken farm, envisioning a quieter rural livelihood after leaving Disney. However, the pull of cartooning quickly drew him back, leading to a long and prolific association with Western Publishing/Dell. Beginning with his first solo story, “The Victory Garden” (April 1943), Barks handled nearly every stage of production—writing tightly crafted scripts, penciling expressive characters and dynamic backgrounds, inking with precision, and hand‑lettering dialogue and captions.

Over the next two decades, he created hundreds of one‑page gags, monthly ten‑pagers for Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories—whose circulation at its peak reached about three million copies—and expansive 24–32‑page adventure epics for Four Color and, later, Uncle Scrooge. These tales blended humor, action, and intricate plotting, often informed by Barks’s meticulous research into geography, history, and culture, lending authenticity and richness to Donald, Scrooge, and their companions’ far‑flung escapades.

Craft & Themes

Barks’s “everyman” Donald wrestled with everyday frustrations in the ten‑pagers, while the longer tales sent the duck clan to deserts, jungles, Arctic wastes, and lost civilizations—settings that showcased Barks’s lush backgrounds and research‑driven details. The tone blended satire, irony, and human warmth.

Duckburg & the Cast

Barks systematically expanded Duckburg into a living world. Key creations include:

- Scrooge McDuck (1947) — flinty, self‑made magnate whose motto was being “tougher than the toughies and smarter than the smarties.”

- Gladstone Gander (1948) — Donald’s infuriatingly lucky cousin.

- Beagle Boys (1951) — persistent bank‑robbery clan.

- Junior Woodchucks (1951) — scout‑like organization for Huey, Dewey, and Louie.

- Gyro Gearloose (1952) — genial, impractical inventor and his Little Helper.

- Cornelius Coot (1952) — Duckburg’s founder.

- Flintheart Glomgold (1956) and John D. Rockerduck (1961) — rival tycoons.

- Magica De Spell (1961) — stylish sorceress fixated on Scrooge’s Number One Dime.

Landmark Stories (Selected)

- “Lost in the Andes!” (1949)

- “A Christmas for Shacktown” (1952)

- “Only a Poor Old Man” (Uncle Scrooge #1, 1952)

- “Back to the Klondike” (1953) — introduces Glittering Goldie

- “Tralla La” (1954)

- “The Golden Helmet” (1952)

- “Land Beneath the Ground!” (1956)

- “Island in the Sky” (1960)

- “North of the Yukon” (1965)

“No Longer Anonymous” (1960s)

Disney/Western creators were uncredited in print, but by 1960 fanzines, amateur press associations, and a small but passionate network of dedicated readers had painstakingly traced the identity of “The Good Duck Artist” to Barks through stylistic analysis, recurring signature elements, and occasional behind-the-scenes hints from industry insiders. As word spread, visits from enthusiastic fans—some traveling great distances to meet him—and the burgeoning convention culture of the 1960s and early 1970s cemented his stature, transforming him from an anonymous craftsman into a revered figure within both fan communities and the wider comics industry.

Third Marriage & Fine Art (1952–1970s)

Barks met accomplished landscape painter Margaret “Garé” Williams at an art show in 1952; their shared love of art and nature quickly blossomed into a partnership, and they married in 1954. Garé, who had formal training in fine arts and a background in both plein‑air painting and commercial illustration, became an essential creative collaborator. She assisted Barks with tasks such as filling solid blacks, refining backgrounds, and hand‑lettering dialogue, enabling him to maintain his demanding production schedule while preserving the crisp quality of his linework.

Following Barks’s official drawing retirement in 1966 (though he continued to script new stories), the couple shifted focus to producing oil paintings inspired by landscapes, wildlife, and later, Disney ducks, selling them at local and regional art shows. Their work gained a loyal collector base, leading to a 1971 Disney license that allowed Barks to create a series of limited‑edition oils featuring beloved duck characters and scenes from his comics.

These works were eagerly sought after, blending fine‑art techniques with the charm of his storytelling. Although the license was briefly suspended due to a dispute over unauthorized reproductions, permission was later reinstated for carefully supervised special projects, further cementing Barks and Garé’s legacy in both the comics and art collecting worlds.

Books, Reprints & Another Rainbow / Gladstone (1970s–1990s)

- Uncle Scrooge McDuck: His Life and Times (1981) collected classic Barks tales—an influential template for prestige comics volumes.

- Another Rainbow Publishing (Bruce Hamilton & Russ Cochran) issued The Fine Art of Walt Disney’s Donald Duck by Carl Barks and the definitive Carl Barks Library (1984–1990; 30 oversized B/W hardcovers).

- Gladstone Publishing (founded 1985) revived Disney comics in the U.S., reprinting Barks, Paul Murry, Floyd Gottfredson, and debuting modern talents; later produced the Carl Barks Library in Color and ancillary art editions.

- Barks made limited public appearances (San Diego Comic‑Con 1977, 1982; European museum tours in the 1990s) and created outlines/scripts later drawn by other artists (e.g., “Horsing Around with History”).

Final Years & Death (1990s–2000)

Widowed in 1993, Barks settled in Grants Pass, Oregon, a quiet community where he continued to paint, correspond with fans worldwide, and occasionally make public appearances despite his advancing age. Diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukemia in 1999, he declined aggressive treatment in 2000, choosing instead to spend his remaining months surrounded by close friends, family, and his artwork. On August 25, 2000, at the age of 99, he passed away peacefully in his home, leaving behind an extraordinary creative legacy cherished by generations of readers and artists.

Influence & Cultural Footprint

- Film & TV: Raiders of the Lost Ark’s opening boulder trap echoes “Seven Cities of Cibola” (1954); DuckTales adapted numerous plots and characters.

- International impact: Europe in particular celebrated Barks as a master storyteller; streets in the Netherlands (e.g., Carl Barksweg) honor his legacy.

- Science & tech curios: A 1949 ten‑pager suggested raising a sunken yacht with ping‑pong balls; decades later engineers performed a similar feat with plastic spheres.

- Astronomy: Asteroid 2730 Barks (1983) commemorates him.

- Manga: Osamu Tezuka cited Barks’s pirate‑gold capers among his early influences.

Selected Filmography (Story Dept.)

Highlights include: Modern Inventions (1937) — a satirical short poking fun at futuristic gadgets; Donald’s Nephews (1938) — introducing Huey, Dewey, and Louie to audiences; Good Scouts (1938) — a Junior Woodchucks‑style outdoor adventure; Mr. Duck Steps Out (1940) — featuring Donald’s romantic pursuit of Daisy Duck; Timber (1941) — a comical conflict between Donald and a lumberjack; Old MacDonald Duck (1941) — Donald as a hapless farmer; Chef Donald (1941) — where Donald’s cooking antics cause chaos; The Vanishing Private (1942) — a World War II‑era camouflage gag story; and Trombone Trouble (1944) — with slapstick musical mayhem involving gods Jupiter and Vulcan.

Awards & Honors (Selected)

- Will Eisner Hall of Fame (1987)

- Jack Kirby Hall of Fame (1987)

- Disney Legends (1991); Duckster (1971)

- Inkpot Award (1977)

- Academy of Comic Book Arts Hall of Fame (1973)

- Shazam Award — Best Writer (Humor Division) (1970)

- Comics Buyer’s Guide Fan Awards (1996)

Tools & Technique

Barks prized clarity, rhythm, and an unbroken visual flow that served both humor and narrative pacing. He inked with Esterbrook dip pens (notably the #356), praising their flexibility in shifting from delicate hairline fades to bold, confident sweeps, and he lettered entirely by hand, often experimenting with subtle variations in letter size and balloon shape to match tone and emotion.

He meticulously planned page turns for maximum comedic or dramatic impact, ensuring that a gag’s payoff or a scene’s surprise landed precisely as the reader flipped the page. His strategic black spotting not only added depth and atmosphere but also acted as a visual guide, directing the reader’s eye smoothly through even the most densely packed action sequences without sacrificing clarity.

Timeline (Condensed)

- 1901 — Born near Merrill, OR

- 1916 — Leaves school; mother dies

- 1920s — Magazine gags; Calgary Eye‑Opener editor

- 1935–42 — Disney Studios, story dept.

- 1942 — Pirate Gold; leaves Disney

- 1943–66 — Dell/Western peak: ten‑pagers & adventures; builds Duckburg

- 1954 — Marries Garé Williams

- 1966 — Retires from drawing new stories; continues scripting

- 1971 — Disney license for duck oils

- 1981 — Uncle Scrooge: His Life and Times

- 1984–90 — Carl Barks Library

- 1991 — Disney Legend

- 2000 — Dies in Grants Pass, OR

Essential Reading (Starter List)

- Only a Poor Old Man (Uncle Scrooge #1)

- Back to the Klondike

- Lost in the Andes!

- A Christmas for Shacktown

- The Golden Helmet

- Tralla La

- North of the Yukon

FAQ about Carl Barks

Q: Why was Carl Barks called “The Good Duck Artist”?

A: Because for decades his stories were published without creator credits, fans who recognized his superior storytelling and art began referring to him as “The Good Duck Artist” to distinguish his work from other anonymous Disney comic creators.

Q: What characters did Carl Barks create?

A: Barks created Scrooge McDuck, the Beagle Boys, Gyro Gearloose, Magica De Spell, Flintheart Glomgold, Gladstone Gander, the Junior Woodchucks, and many others that became central to the Duckburg universe.

Q: How did Barks influence popular culture?

A: His adventure plots inspired scenes in films like Raiders of the Lost Ark, his characters shaped DuckTales, and his treasure-hunt and globe-trotting themes influenced storytelling across comics, animation, and even video games.

Q: Was Carl Barks involved in animation?

A: Yes, before his comic book career, Barks worked in Disney’s story department on Donald Duck shorts, contributing gags, storyboards, and ideas that defined the character’s personality on screen.

Q: How can I read Carl Barks’s stories today?

A: His work is available in collected editions such as the Carl Barks Library, the Carl Barks Library in Color, and ongoing reprints from publishers like Fantagraphics.

Q: Did Carl Barks win awards?

A: Yes, he was inducted into the Will Eisner Hall of Fame, the Jack Kirby Hall of Fame, named a Disney Legend, and received numerous other accolades recognizing his influence on comics and popular culture.

This post was created with our nice and easy submission form. Create your post!