Osamu Tezuka (手塚 治虫, born 3 November 1928; died 9 February 1989) is widely regarded as one of the most influential creators in the history of manga and Japanese animation. Over a career spanning the postwar decades, Tezuka reshaped how comics could look, move, and feel—not only in Japan, but eventually across the globe. His reputation as “the god of manga” rests on both scale and innovation: a vast body of work, new storytelling grammar inspired by cinema, and a restless willingness to reinvent himself from children’s adventure tales to adult, unsettling gekiga-era dramas.

In the public imagination—especially outside Japan—Tezuka is often described as the “Japanese Walt Disney.” That comparison isn’t baseless: Tezuka openly admired Disney films, and his early character designs helped normalize the large-eyed expressiveness that became synonymous with anime. But the Disney analogy can also flatten Tezuka’s legacy. Tezuka didn’t just create lovable icons like Astro Boy (Tetsuwan Atom) and Kimba the White Lion (Jungle Emperor)—he also produced deeply adult, morally complex works such as Black Jack, Phoenix, Message to Adolf, and MW, which confront war, racism, identity, medical ethics, and the darker corners of human desire.

Writing for Toons Mag, I’ve noticed a pattern whenever Tezuka comes up: readers tend to know him through one doorway—often Astro Boy—and then feel stunned when they discover the other rooms in the house. This is one reason Tezuka still matters. He’s not simply a “founder” or “origin point.” He’s a case study in how a creator can evolve with (and sometimes against) a culture, while building the industry infrastructure that makes future creativity possible.

What follows is a detailed, historically grounded look at Tezuka’s life and work: his upbringing and influences, his postwar breakthrough, his invention of a modern manga storytelling language, his pioneering studio model for TV anime, his turn toward gekiga and adult themes, and the long shadow he continues to cast over global comics and animation.

Osamu Tezuka (手塚 治虫)

| Full name | Osamu Tezuka (手塚 治虫) |

| Born | November 3, 1928 |

| Birthplace | Toyonaka, Osaka Prefecture, Japan |

| Died | February 9, 1989 (age 60) |

| Deathplace | Tokyo, Japan |

| Cause of death | Stomach cancer |

| Nationality | Japanese |

| Occupations | Manga artist, cartoonist, animator, film producer (also trained as a medical doctor) |

| Years active | 1946–1989 |

| Known for | Pioneering modern manga + early TV anime production |

| Famous titles | Astro Boy (Tetsuwan Atom), Black Jack, Phoenix (Hi no Tori), Buddha, Princess Knight (Ribon no Kishi), Kimba the White Lion (Jungle Emperor), Message to Adolf, Dororo, MW |

| Notable companies | Mushi Production (founded 1961), Tezuka Productions (founded 1968) |

| Artistic traits | “Cinematic” paneling; expressive faces; genre innovation (kids’ classics + adult gekiga-era works) |

| Nicknames | “God of Manga,” “Father/Godfather of Manga” |

| Legacy | Tezuka Osamu Manga Museum (Takarazuka); Tezuka Osamu Cultural Prize; global influence on manga/anime storytelling |

Why Tezuka’s name sits at the center of manga and anime history

Tezuka’s importance is sometimes summarized in one sentence: he modernized manga and helped industrialize anime. But that summary misses the deeper point: Tezuka didn’t merely “add” techniques—he changed expectations.

He normalized cinematic storytelling in manga

Tezuka popularized page compositions that feel like film editing—close-ups, establishing shots, “camera” movement across panels, dramatic pacing through silent sequences, and emotionally legible facial acting. This approach is frequently discussed as a key ingredient in the postwar “manga revolution.”

He proved manga could carry multiple genres at scale

Tezuka’s bibliography includes children’s adventure, romance, historical epics, science fiction, medical drama, Buddhist biography, political thriller, horror, satire, and experimental short fiction—demonstrating that manga could be a mass medium without being a single-genre medium.

He helped establish the production model that made TV anime sustainable

When Tezuka founded Mushi Production and launched Astro Boy (1963), the series became a foundational example of how weekly TV animation could be produced under tight schedules and constrained budgets—using approaches that later became associated with anime production.

He expanded manga’s moral and emotional range

Tezuka’s shift into adult-oriented work—especially from the late 1960s onward—shows a creator testing how far the medium can go: not just entertainment, but ethics; not just fantasy, but history; not just heroes, but compromised protagonists.

Early life in Osaka Prefecture: family, illness, and the seeds of a worldview (1928–1945)

Osamu Tezuka was born in Toyonaka, Osaka Prefecture, and spent formative years in and around Takarazuka, a city that later became closely associated with his memory and public legacy.

Two forces shaped young Tezuka in especially lasting ways:

1. Visual wonder: Disney films and the idea that drawings could breathe

Tezuka’s early fascination with animation—especially Disney—helped form his obsession with movement, facial expressiveness, and emotional clarity. The “big eyes” style often associated with Tezuka is commonly explained as part of this cross-cultural conversation: Western animation influenced Tezuka, and Tezuka’s stylization later influenced Japanese animation and, indirectly, the world.

2. The performing arts: Takarazuka Revue and theatrical emotion

Takarazuka’s famous all-female theater culture is repeatedly cited as an influence on Tezuka’s later costume designs, romantic dramatics, and character staging. Even when his stories became darker, his sense of “performance”—a character entering a scene, delivering a rhythm, owning the spotlight—remained.

Tezuka also experienced illness as a child, and later trained in medicine—two biographical facts that matter when you read works like Black Jack or Ode to Kirihito, where bodies become battlegrounds for ethics, power, compassion, and identity.

Early life Summary (1928–1945)

Tezuka was the eldest of three children in Toyonaka, Osaka. The Tezuka family were prosperous and well-educated; his father Yutaka worked in management at Sumitomo Metals, his grandfather Taro was a lawyer, and his great-grandfather Ryoan and great-great-grandfather Ryosen were doctors. His mother’s family had a long military history. Tezuka’s nickname was gashagasha-atama (gashagasha is slang for messy, atama means head). Later in life, he gave his mother credit for inspiring confidence and creativity through her stories.

She frequently took him to the Takarazuka Grand Theater, which often headlined the Takarazuka Revue, an all-female musical theater troupe. Their romantic musicals aimed at a female audience had a large influence on Tezuka’s later works, including his costume designs. Not only that, but the large, sparkling eyes also had an influence on Tezuka’s art style. He has said that he has a profound “spirit of nostalgia” for Takarazuka.

When Tezuka was young, his father showed him Disney films; he became obsessed with the films and began to replicate them. He also became a Disney movie buff, seeing the films multiple times in a row, most famously seeing Bambi more than 80 times. Tezuka started to draw comics around his second year of elementary school, drawing so much that his mother would have to erase pages in his notebook in order to keep up with his output. Tezuka was also inspired by works by Suihō Tagawa and Unno Juza. Around his fifth year, he found a bug named “Osamushi”.

It so resembled his name that he adopted “Osamushi” as his pen name. He continued to develop his manga skills throughout his school career. During this period he created his first adept amateur works. During high school in 1944, Tezuka was drafted to work for a factory, supporting the Japanese war effort during World War II; he simultaneously continued writing manga. In 1945, Tezuka was accepted into Osaka University and began studying medicine. During this time, he also began publishing his first professional works.

Postwar Japan and the “manga revolution”: why New Treasure Island mattered (1946–1947)

After World War II, Japan’s publishing landscape—and its youth culture—changed rapidly. Manga existed before Tezuka, but the postwar moment created a hunger for new forms of mass entertainment and new narrative intensity.

Tezuka’s early breakthrough is often linked to Shin Takarajima (New Treasure Island), published in the immediate postwar era (commonly dated to 1947 in many histories). The book’s legacy is frequently discussed as a turning point, not because it invented comics, but because it demonstrated a new kind of pacing and cinematic excitement that young readers devoured.

If you want a practical way to understand why New Treasure Island is so often cited: it helped convince publishers and readers that manga could be propulsive, modern, and emotionally immersive—not only gag strips or short children’s stories, but something closer to an experience.

Publishing career and early success (1946–1952)

Tezuka came to the realization that he could use manga as a means of helping to convince people to care for the world. After World War II, at age 17, he published his first piece of work: Diary of Ma-chan. Tezuka began talks with fellow manga artist Shichima Sakai, who had pitched Tezuka a manga based around the famous story Treasure Island. Sakai promised Tezuka a publishing spot from Ikuei Shuppan if he would work on the manga.

Tezuka finished the manga, only loosely basing it on the original work. Shin Takarajima (New Treasure Island) was published and became an overnight success that began the golden age of manga, a craze comparable to American comic books at the time. In 1951, Tezuka joined a group known as the Tokyo Children Manga Association consisting of other manga artists such as Baba Noboru, Ota Jiro, Furusawa Hideo, Fukui Eiichi, Irie Shigeru, and Negishi Komichi. With the success of New Treasure Island, Tezuka traveled to Tokyo in search of a publisher for more of his work. After visiting Kobunsha Tezuka was turned down.

However, publisher Shinseikaku agreed to purchase The Strange Voyage of Dr. Tiger and Domei Shuppansha would purchase The Mysterious Dr. Koronko. Whilst continuing his study in medical school Tezuka published his first masterpieces: a trilogy of science fiction epics called Lost World, Metropolis and Next World. Soon after Tezuka published his first major success Jungle Emperor Leo, it was serialized in Manga Shonen from 1950 to 1954. In 1951 Tezuka graduated from the Osaka School of Medicine and published Ambassador Atom, the first appearance of the Astro Boy character.

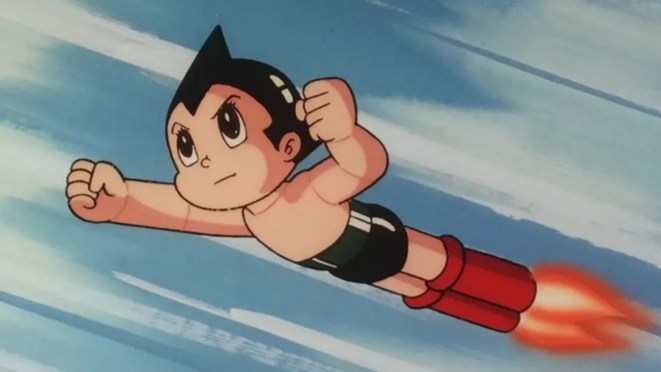

Astro Boy and the birth of a national icon (1952 onward)

From “Ambassador Atom” to Tetsuwan Atom

Astro Boy’s roots trace to early Tezuka work, but Tetsuwan Atom (Astro Boy) became the cultural eruption: a robot child with moral agency navigating a world where humans and machines collide.

In Tezuka’s hands, Astro Boy wasn’t merely a cute character—he was a narrative engine for questions Japan was facing in the mid-20th century:

- How do we rebuild after catastrophe?

- What does “progress” cost?

- How do prejudice and fear form?

- Can technology be humanized—or will humans become mechanized?

These aren’t abstract themes pasted on top of action. They’re baked into Astro Boy’s premise: a powerful being with a child’s heart, constantly forced to arbitrate between violence and compassion.

Astro Boy, national fame and early animation (1952–1960)

By 1952, Ambassador Atom proved to be an only mild success in Japan; however, one particular character became extremely popular with young boys: a humanoid robot named Atom. Tezuka received several letters from many young boys. Expecting success with a series based around Atom, Tezuka’s producer suggested that he be given human emotions. One day while working at a hospital Tezuka was punched in the face by a frustrated American G.I. This encounter gave Tezuka the idea to create an Atom.

On February 4, 1952, Tetsuwan Atom began serialization in Weekly Shonen Magazine. The character Atom and his adventures became an instant phenomenon in Japan. Due to the success of Tetsuwan Atom, in 1953 Tezuka published shōjo manga Ribon no Kishi (Princess Knight), serialized in Shojo Club from 1953 to 1956. In 1954 Tezuka first published what he would consider his life’s work, Phoenix, which originally appeared in Mushi Production Commercial Firm.

In 1958 Tezuka was asked by Toei Animation if his manga Son-Goku The Monkey could be adapted into an animation. It was widely reported that Tezuka worked as a director on the film, though Tezuka himself denied working on it. He was only involved in its promotion, which later sparked his interest in the animation industry. The film was released as Alakazam the Great in 1960.

Astro Boy (1963): the TV series that changed the industry

The 1963 Astro Boy anime—produced by Tezuka’s Mushi Production—became one of the most important early Japanese TV animated series, running for years and reaching audiences beyond Japan.

It’s hard to overstate what this meant in practice:

- A weekly production rhythm demanded new workflows.

- Budget pressure encouraged “limited animation” strategies.

- Popular success proved there was a mass audience for serialized animated storytelling.

Scholars and historians debate the nuance of “firsts” and the mythmaking around early TV anime, but the core point stands: Astro Boy helped define the model that later studios would refine and react against.

Princess Knight: gender performance, identity, and shōjo storytelling (1953–1956)

One of Tezuka’s most historically important achievements is Ribon no Kishi (Princess Knight)—a shōjo series that blends fairy-tale romance with questions of gender identity and social role.

Even readers encountering it decades later can see why it matters:

- The heroine is forced to navigate identity as performance.

- Court politics and romance share space with action adventure.

- Emotional interiority becomes central, not secondary.

Whether or not one calls it the “origin” of modern shōjo conventions, it’s clearly foundational—both aesthetically and structurally—and it demonstrates Tezuka’s ability to build new audience lanes for manga.

Kimba the White Lion and the nature of innocence in a violent world (1950s)

Jungle Emperor (Kimba the White Lion) is often remembered for its animal cast and grand emotional arcs. But it also reveals something about Tezuka’s worldview: he repeatedly returned to nature as moral witness—an arena where human ambition, cruelty, and hope play out in allegorical form.

This “love for nature” theme is explicitly highlighted in discussions of Tezuka’s legacy institutions in Takarazuka, reinforcing that his environmental and humanist concerns were not late additions—they were persistent throughlines.

Phoenix: Tezuka’s lifelong project about death, rebirth, and what history does to us

If Astro Boy is Tezuka’s most famous child of science fiction, Phoenix (Hi no Tori) is his philosophical epic: a series about immortality, suffering, cycles of violence, and spiritual longing, told across multiple eras and genres.

Tezuka himself regarded Phoenix as a central work, and its multi-arc structure—jumping across time—makes it feel like Tezuka is wrestling with the same haunting question again and again:

If humans keep repeating cruelty, can we still believe in progress?

Phoenix is also a key example of why the “Japanese Disney” label collapses under pressure. Disney is a meaningful influence on Tezuka’s early visual vocabulary, but Phoenix belongs to a different literary universe—closer to myth, moral philosophy, and historical tragedy than to family entertainment.

Medicine and manga: Tezuka’s scientific training and the ethics of Black Jack

Tezuka’s biography contains an uncommon duality: he trained in medicine and later used scientific knowledge to enrich his fiction.

Official Tezuka timelines note a medical doctorate milestone in 1961 (Nara Medical University), underscoring that medicine wasn’t merely an abandoned path—it remained part of his intellectual formation.

Why that matters for Black Jack

Black Jack is one of the most influential medical dramas in comics. Its central character—an unlicensed genius surgeon—operates in moral gray zones. Stories often ask:

- Who deserves care?

- What does money do to ethics?

- Can a doctor be righteous while breaking the law?

- Is “saving a life” always the highest good?

Black Jack’s popularity suggests something profound: Tezuka used medical melodrama not just for suspense, but to explore how modern systems fail vulnerable people.

Mushi Production: Tezuka as industry builder, not only storyteller (1961–1973)

Tezuka founded Mushi Production (often credited as established in the early 1960s), launching a new chapter where he was not only an artist but also a producer shaping the business of animation.

This pivot matters for two reasons:

- It brought Tezuka’s storytelling instincts into motion—literal movement, sound, timing.

- It created a training ground—a workplace whose later fragmentation and financial collapse still influenced the industry.

Accounts of Mushi’s financial struggles and bankruptcy in 1973 appear repeatedly in animation histories, with the fallout contributing to the formation and staffing of other studios.

In other words, Tezuka’s influence isn’t only what he drew—it’s also the human network and production logic that spread outward from his studios.

Tezuka Productions: preserving a creator’s universe as living IP (1968 onward)

After stepping away from a direct leadership role at Mushi, Tezuka founded Tezuka Productions in 1968, which remains central to managing and licensing his creations while also producing animation.

This is an early example of something now common across global entertainment: the idea that a creator’s “world” can outlive them through careful stewardship—new editions, adaptations, exhibitions, and controlled collaborations.

It also connects to why Tezuka’s legacy is unusually visible today: there is an organized institution ensuring that his work stays in circulation and that new generations meet him not as an obscure pioneer, but as a continuing presence.

The gekiga era: Tezuka’s “second life” as a darker, adult storyteller (late 1960s–1980s)

One of the most misunderstood aspects of Tezuka’s career is the narrative that he “peaked” with children’s works. In reality, the late 1960s onward marks a second artistic identity: Tezuka responding to the rise of gekiga, adult magazines, and a readership hungry for realism and confrontation.

Rather than rejecting the movement, Tezuka competed, adapted, and transformed.

Works often discussed in this adult phase include Ayako, Ode to Kirihito, Apollo’s Song, The Book of Human Insects, MW, Message to Adolf, and others—stories filled with violence, crime, psychological damage, political dread, and moral contamination.

Why this shift matters historically

This period shows Tezuka doing something rare: refusing to become a “brand” trapped in his own early style. He proved that a mass-popular creator could risk alienation in order to keep evolving.

As a critic, I think this is the most instructive lesson Tezuka offers modern creators: if your medium changes, you either argue with it or you fossilize. Tezuka argued—with energy.

Production Career (1961-1989)

In 1961, Tezuka entered the animation industry in Japan by founding the production company Mushi Productions as a rivalry with Toei Animation. He first began innovating the industry with the broadcast of the animated version of Astro Boy in 1963; this series would create the first successful model for animation production in Japan and would also be the first Japanese animation dubbed into English for an American audience. Other series were subsequently translated to animation, including Jungle Emperor, the first Japanese animated series produced in full color.

Tezuka stepped down as acting director in 1968 to found a new animation studio, Tezuka Productions and continued experimenting with animation late into his life. In 1973, Mushi Productions collapsed financially and the fallout would produce several influential animation production studios including Sunrise.

His gekika graphic novels (1967-1989)

In 1967, in response to the magazine Garo and the gekiga movement, Tezuka created the magazine COM. Together with this, he radically changed his style as a comic book artist from the cartoony Disney-esque slapstick towards a more realistic drawing style as well as the themes of these books became focused on an adult audience.

Besides the well known series Phoenix, Black Jack and Buddha that are drawn in this style he also produced a vast amount of one-shots or shorter series like Ayako, Ode to Kirihito, Message to Adolf, Swallowing the Earth, Alabaster, Apollo’s Song, Barbara, MW, Dororo, I.L., Ludwig B, The Book of Human Insects and a large amount of short stories that were later on collectively published in books as Under the Air, Clockwork Apple, The Crater, Melody of Iron and other short stories, Record of the Glass Castle.

The change of his manga from children to more ‘literary’ gekiga manga started with the yokai manga Dororo in 1967. This yokai-manga was influenced by the success of and response to Shigeru Mizuki’s GeGeGe no Kitarō. Simultaneously he also produces Vampires that, like Dororo also introduces a stronger, more coherent storyline and a shift in the drawing style. After these two he starts his really first gekiga attempt with Swallowing the Earth. Dissatisfied with the result he soon after produces I.L. (not published in English yet). Also his masterpiece Phoenix starts in 1967.

A vast amount of one-shots and short series follows in the years after Ode to Kirihito, Alabaster, Apollo’s Song, Barbara, Ayako, the Book of Human Insects are all gekiga graphic novels from this area. Under the Air, The Crater, Clockwork Apple, Melody of Iron and Record of the Glass Castle are collections of short gekiga stories that were drawn in those same years. A common element in all these books and short stories is the very dark immoral nature of the main characters. Also, the stories are filled with explicit violence, erotic scenes, and crimes.

Probably the most depraved story of this area is MW (1976). Tezuka would become a bit milder in narrative tone in the 80s with his follow up works such as Message to Adolf, Midnight and (the unfinished) Ludwig B and Neo Faust.

Tezuka is a descendant of Hattori Hanzō, a famous ninja and samurai who faithfully served Tokugawa Ieyasu during the Sengoku period in Japan. His son Makoto Tezuka became a film and anime director. Tezuka guided many well-known manga artists such as Shotaro Ishinomori and Go, Nagai. Tezuka enjoyed bug-collecting, entomology, Walt Disney, baseball, and licensed the “grown-up” version of his character Kimba the White Lion as the logo for the Seibu Lions of the Nippon Professional Baseball League. Tezuka met Walt Disney in person at the 1964 New York World’s Fair.

In a 1986 entry in his personal diary, Tezuka stated that Disney wanted to hire him for a potential science fiction project. Tezuka was a fan of Superman and was made the honorary chairman of the Superman Fan Club in Japan. In 1959 Tezuka married Etsuko Okada at a Takarazuka Hotel. As a child, Tezuka’s arms swelled up and he became ill. He was treated and cured by a doctor, which made him want to be a doctor. At a crossing point, he asked his mother whether he should look into doing manga full-time or whether he should become a doctor.

At the time, being a manga author was not a particularly rewarding job. The answer his mother gave was: “You should work doing the thing you like most of all.” Tezuka decided to devote himself to manga creation on a full-time basis. He graduated from Osaka University and obtained his medical degree, but he would later use his medical and scientific knowledge to enrich his sci-fi manga, such as Black Jack. Tezuka was agnostic and was buried in a Buddhist cemetery in Tokyo.

Works

His complete oeuvre includes over 700 volumes with more than 150,000 pages. A complete list of his works can be found on the Tezuka Osamu Manga Museum website. Tezuka’s creations include Astro Boy (Mighty Atom in Japan), Black Jack, Princess Knight, Phoenix (Hi no Tori in Japan), Kimba the White Lion (Jungle Emperor in Japan), Unico, Message to Adolf, The Amazing 3 and Buddha. His “life’s work” was Phoenix—a story of life and death that he began in the 1950s and continued until his death.

In January 1965, Tezuka received a letter from American film director Stanley Kubrick, who had watched Astro Boy and wanted to invite Tezuka to be the art director of his next movie, 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). Although flattered by Kubrick’s invitation, Tezuka could not afford to leave his studio for a year to live in England, so he had to turn it down. Although he could not work on it, he loved the film and would play its soundtrack at maximum volume in his studio to keep him awake during long nights of work.

Style

Tezuka is known for his imaginative stories and stylized Japanese adaptations of western literature. Tezuka’s “cinematic” page layouts were influenced by Milt Gross’ early graphic novel He Done Her Wrong. He read this book as a child, and its style characterized many manga artists who followed in Tezuka’s footsteps. His work, like that of other manga creators, was sometimes gritty and violent.

Tezuka headed the animation production studio Mushi Production (“Bug Production”), which pioneered TV animation in Japan. He invented the distinctive “large eyes” style of Japanese animation, drawing inspiration from Western cartoons and animated films of the time such as Betty Boop, Mickey Mouse, and other Disney movies.

Technique: Tezuka’s storytelling tools that became industry language

Tezuka’s influence is sometimes described like this: “big eyes, cinematic panels.” True—but incomplete. The deeper influence is structural.

1. Panel rhythm and “silent acting”

Tezuka often lets panels breathe without text—faces, gestures, pauses. That silence becomes emotional punctuation.

2. Character acting over exposition

Even in science fiction, Tezuka pushes emotion through expressions, body language, and staging rather than constant explanation.

3. Genre as a laboratory

He treated genres as tools, not cages: he could use medical drama to talk about capitalism, or sci-fi to talk about prejudice, or historical fiction to dissect nationalism.

4. Moral complexity as narrative fuel

Tezuka’s adult work especially uses compromised characters to keep the reader in a state of ethical tension: you’re rarely allowed to feel comfortably righteous.

“Japanese Walt Disney”: what the comparison gets right—and what it obscures

It’s reasonable to acknowledge Disney’s impact on Tezuka’s formative imagination. Tezuka’s admiration for Western animation is widely documented, and the emotional clarity of Disney storytelling clearly appealed to him.

But here’s what the Disney analogy can hide:

- Tezuka’s adult bibliography is far more overtly political and sexually mature than Disney’s mainstream output.

- Tezuka’s work repeatedly interrogates modernity itself—technology, war, institutional power.

- Tezuka did not only build “family entertainment”; he also built manga as a vehicle for philosophical and social critique.

So a more useful framing might be: Tezuka absorbed Disney’s craft and then wrote a different kind of humanist literature with it.

The Kubrick invitation: a revealing “what if” (and why it fits Tezuka’s mythos)

A famous anecdote claims that Stanley Kubrick invited Tezuka to work on 2001: A Space Odyssey, which Tezuka declined due to commitments and workload. This story appears in multiple places and is even referenced in popular media databases, but details vary and it’s difficult to treat every version as equally verifiable.

Whether one treats it as fully documented fact or a highly plausible anecdote amplified over time, the reason it persists is telling: Tezuka feels like the kind of creator Kubrick would have recognized—someone obsessed with the future, with ethics, with how images think.

For a Toons Mag readership, the key takeaway isn’t celebrity trivia. It’s this: Tezuka was already global in imagination, even before global fandom had a name.

Death in 1989 and the public response: the artist who begged to keep drawing

Tezuka died in Tokyo on 9 February 1989.

One of the most repeated accounts of his last moments is that he pleaded to keep working—often quoted as “I’m begging you, let me work!” The line is widely circulated, but many English-language retellings trace through secondary biographies and anecdotes rather than a single definitive primary transcript, so it’s best understood as a widely reported recollection rather than a courtroom-grade quotation.

Still, the line endures because it matches what we can document: Tezuka’s output, his relentless schedule, and the fact that unfinished chapters of Phoenix remained when he died.

Institutions of remembrance: the Tezuka Osamu Manga Museum in Takarazuka

Tezuka’s relationship with Takarazuka is central to how Japan remembers him publicly. The city opened the Tezuka Osamu Manga Museum / Memorial Hall in April 1994, turning his legacy into a physical cultural space—part archive, part exhibition, part workshop.

The museum’s themes—often summarized around love for nature and the preciousness of life—echo the moral core of Tezuka’s work.

Awards and honors: how Tezuka’s reputation became institutional

Tezuka received numerous honors in life and posthumously, and his status only grew after his death. Modern awards named after him—such as the Tezuka Osamu Cultural Prize—signal how he functions as a benchmark: a way for Japan to recognize manga as literature and art.

Internationally, his work continues to be recognized through translated editions and awards attention (for example, Eisner-related recognition for certain translated volumes is discussed in reference sources).

Tezuka’s global influence: direct inspiration, indirect DNA, and the creators who followed

Tezuka’s influence does not travel in only one form. It spreads through:

- Direct influence (artists citing him explicitly)

- Industrial inheritance (TV anime workflows and production logic)

- Aesthetic inheritance (expressive acting, cinematic paneling)

- Thematic inheritance (humanism, ethical conflict, anti-war sentiment)

Even when contemporary creators move far from Tezuka’s art style, they often inherit his belief that comics can handle “big” subjects without losing entertainment value.

A reading roadmap: where to start with Tezuka (and why each path matters)

Osamu Tezuka wrote so much—and with such range—that “start with the best one” is honestly the wrong advice. A better question is: what kind of reader are you right now? Tezuka built an entire library wing, not a single shelf—and each doorway teaches you something different about why his work still matters.

Below are six practical entry paths I recommend, each with a purpose—and a quick note on what you’ll actually learn about Tezuka (and comics) by taking it.

If you want foundational pop culture

Start with: Astro Boy (manga + the 1963 anime context)

If your goal is to understand why Tezuka is called the “God of Manga,” Astro Boy is the cleanest “origin point.” The manga began in 1952 and ran through the 1960s in various forms, becoming one of the defining works of modern Japanese popular culture.

Then jump to the 1963 TV anime—not because it’s the “best-looking” (it’s early TV animation), but because it’s historically pivotal: it premiered January 1, 1963, ran for 193 episodes, and is widely cited as the first popular Japanese TV series to embody the style the world later recognized as “anime.”

Why this path matters:

You’re seeing Tezuka’s belief that mass entertainment can still carry moral weight—robots, civil rights, war anxiety, discrimination, the ethics of technology—delivered in a form kids could love and adults could respect. It’s “pop,” but it’s not empty.

Best for readers who like: clean heroism, sci-fi morality plays, early anime history.

Then: Kimba the White Lion (Jungle Emperor)

If Astro Boy is Tezuka’s science-and-justice pillar, Kimba is his nature-and-leadership pillar. The manga was serialized from November 1950 to April 1954, and the anime adaptation followed later.

Why this path matters:

It shows Tezuka building a broad, emotional saga around ecology, governance, interspecies conflict, and the costs of “civilizing” nature—well before environmental storytelling became mainstream in global animation.

Best for readers who like: animal epics, ethics of power, “Disney-adjacent” mythic storytelling (with Tezuka’s own logic).

If you want ethical drama and medicine

Start with: Black Jack

This is Tezuka at his most readable in short bursts—medical cases that hit like moral riddles. The manga ran from November 19, 1973 to October 14, 1983 in Weekly Shōnen Champion.

Why this path matters:

Because it’s not “medical manga” as a gimmick. It’s Tezuka using surgery and diagnosis as a storytelling machine for:

- class inequality (“who deserves care?”)

- corruption (“who profits from illness?”)

- consent and dignity (“what does ‘saving’ someone mean?”)

You also see how Tezuka’s medical training doesn’t make the stories cold—it makes them sharper. Black Jack is a clinic where human nature is the real patient.

Best for readers who like: dramatic standalone stories, ethical dilemmas, character-driven intensity.

If you want the philosophical epic

Start with: Phoenix (Hi no Tori)

If Tezuka has one work that functions like a personal religion—this is it. Tezuka began early versions in the mid-1950s, and the series continued in different forms until his death in 1989, remaining unfinished.

Why this path matters:

Because Phoenix is Tezuka refusing to let manga stay small. It’s reincarnation, empire, science, myth, extinction, rebirth—told across eras like a looped argument about what humans do with life when they’re terrified of death.

If you want the “Tezuka who isn’t just a brand,” this is the doorway.

Best for readers who like: big ideas, nonlinear timelines, spirituality without preaching.

If you want adult political and psychological intensity

This is Tezuka’s “dark period” gateway—where he leans into moral rot, state violence, shame, sexuality, identity, and the aftertaste of war.

Try this order (from most historical to most corrosive):

1. Message to Adolf (1983–1985)

Serialized January 6, 1983 to May 30, 1985, this political thriller is built around three men named Adolf—one of them Hitler—using espionage and journalism as engines for a brutally human story about nationalism, ethnicity, and war.

2. MW (1976–1978)

A suspense series serialized from 1976 to 1978, MW is Tezuka proving he can out-dark the “serious” manga movement—chemical weapons, guilt, predation, and the fragile myth of purity.

3. Ayako (1972–1973)

Serialized January 25, 1972 to June 25, 1973, Ayako is a postwar family tragedy—land, money, secrets, institutional cruelty—where “society rebuilding” is shown as another kind of damage.

4. Ode to Kirihito (1970–1971)

Serialized 1970–1971, it’s body horror with medical realism: a doctor investigates a disease that deforms victims into “dog-people,” then becomes entangled in exploitation and cruelty himself.

Why this path matters:

Because it prevents the lazy take that Tezuka is only “big eyes and cute mascots.” These works show him interrogating the ugliest parts of modernity: propaganda, institutions, violence, and how “normal life” can be complicit.

Best for readers who like: historical thrillers, moral ambiguity, bleak psychological drama.

If you want a spiritual and historical lens

Start with: Buddha (1972–1983)

Tezuka’s Buddha ran from September 1972 to December 1983 and remains one of his most widely respected long epics, blending historical fiction, philosophy, humor, and brutality.

Why this path matters:

This is Tezuka using spiritual biography as a way to talk about caste, suffering, power, compassion, and the social mechanics of cruelty—without turning the story into a sermon. It’s accessible and profound at the same time, which is basically Tezuka’s superpower in one sentence.

Best for readers who like: history-based epics, moral inquiry, spiritual narratives grounded in human behavior.

Putting it together: “Tezuka is not a single shelf—he’s a wing.”

If you’re the kind of reader who likes progressive difficulty, here’s a practical “escalation ladder”:

- Astro Boy (foundation + invention of the TV-anime era)

- Black Jack (ethical intensity in bite-sized doses)

- Buddha (big narrative + spiritual history)

- Phoenix (Tezuka’s philosophical ceiling)

- Message to Adolf / MW / Ayako / Ode to Kirihito (the “don’t look away” Tezuka)

Tezuka’s real legacy is not a style—it’s permission

Osamu Tezuka’s lasting influence isn’t only about “big eyes” or iconic mascots. It’s about permission:

- Permission for manga to become cinematic and emotionally ambitious.

- Permission for anime to become serialized, industrial, and globally exportable—with Astro Boy (1963) often cited as a cornerstone in establishing the TV-anime model.

- Permission for comics to confront war, prejudice, medical ethics, sexuality, and existential dread without abandoning popular readability—because Tezuka insisted that entertainment and seriousness don’t have to live in separate rooms.

Tezuka’s genius wasn’t that he “predicted the future” perfectly—it’s that he kept insisting, again and again, that drawing could contain the whole human argument: innocence and corruption, science and spirit, comedy and grief, hope and collapse.

That’s why, decades after his death, Tezuka still feels contemporary. Not because we’re living in his world—but because we’re still asking his questions.

FAQs about Osamu Tezuka

Here are some frequently asked questions (FAQ) about Osamu Tezuka:

Q: Who is Osamu Tezuka?

A: Osamu Tezuka (1928-1989) was a Japanese manga artist, animator, and film producer. He is often called the “Godfather of Manga” and the “God of Manga” due to his immense contributions to the medium and influence on Japanese popular culture.

Q: What is Osamu Tezuka known for?

A: Osamu Tezuka is known for his pioneering work in manga and anime. He created numerous iconic characters and series, such as “Astro Boy,” “Kimba the White Lion,” and “Black Jack.” He also explored various genres, from science fiction and fantasy to historical dramas and social commentary.

Q: What is Tezuka’s significance in manga history?

A: Tezuka revolutionized the manga industry with his innovative storytelling techniques, distinctive art style, and cinematic approach to panel layout. He introduced complex characters, mature themes, and serialized storytelling, raising the artistic and narrative standards of manga.

Q: What is Tezuka’s art style like?

A: Tezuka’s art style is characterized by his use of large, expressive eyes, simplified character designs, and dynamic compositions. His work often features a blend of humor, drama, and action, showcasing his ability to convey a wide range of emotions through his illustrations.

Q: What are some of Tezuka’s notable works?

A: Besides “Astro Boy,” arguably his most famous creation, Tezuka produced numerous acclaimed manga and anime series. Some notable works include “Phoenix,” “Princess Knight,” “Buddha,” “Dororo,” and “Metropolis.” His vast body of work spans over 700 manga titles and more than 200,000 pages.

Q: Has Tezuka’s work been adapted into films and TV series?

A: Yes, many of Tezuka’s manga have been adapted into animated TV series, films, and live-action adaptations. His stories and characters have significantly impacted the anime industry, and his works continue to be adapted and reimagined to this day.

Q: What is Tezuka’s influence on the manga and anime industry?

A: Tezuka’s influence on the manga and anime industry cannot be overstated. His innovative storytelling techniques, complex characters, and socially relevant themes laid the foundation for future generations of manga artists and animators. His works have inspired countless creators and have helped popularize manga and anime worldwide.

Q: Did Tezuka receive any awards for his contributions?

A: Yes, Tezuka received numerous awards throughout his career, including the Shogakukan Manga Award, the Bungei Shunju Manga Award, and the Japan Cartoonists Association Award. In recognition of his exceptional contributions to manga and anime, he also received the Asahi Prize and the Order of the Sacred Treasure from the Japanese government.

Q: Where can I find Tezuka’s manga and anime works?

A: Tezuka’s manga works are widely available in print and digital formats, and many have been translated into multiple languages. Anime adaptations of his works can be found on various streaming platforms, and his influence can be seen in the works of contemporary manga and anime artists.

This post was created with our nice and easy submission form. Create your post!

5 Comments